In the corner of a lab room in Candelaria Hall is a handheld tool that looks similar to a barcode scanner grocery store clerks use at the checkout line. However, this tool is called an X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, and instead of deciphering the price of a cereal box, the XRF determines what elements make up an item it is scanning.

“The technology shoots a low-energy X-ray beam at the item we’re interested in, knocking around the electrons in the atoms, which then send a burst of energy back to the instrument to be measured,” said Associate Professor of Anthropology Marian Hamilton, Ph.D.

Hamilton has been using the XRF at UNC for research and coursework since 2021. The technology is particularly helpful in her paleoecology research, where she can determine the chemical composition in animal teeth and bone fossils, revealing what animals ate when they were alive.

However, Hamilton says the small machine can detect most elements on the periodic table, making the application of the XRF endless.

“The very cool part is that every single element is going to burst back a unique energy signature when its atoms get knocked around, so if we can measure how many little bits of energy called photons come in at each one of these particular energy strengths, we can see what elements are inside any item,” Hamilton said.

As it turns out, some of those elements can be pretty dangerous.

One of the most recent uses of the XRF at UNC was a project dealing with 18th-century books. Angela Naumov, manager of archives and rarebooks atDenver Botanic Gardens, reached out to Hamilton asking if they could collaborate and use the XRF technology to analyze the composition of their rare books within the collection of the Gardens’ Helen Fowler Library.

Naumov said they learned about The Poison Book Project, which focuses on identifying potentially toxic pigments used in bookbinding components and how to handle and store toxic collections more safely. Not knowing if any in their collection contained these dangerous elements, she wanted to do the same for their historic books.

“As our library is part of Denver Botanic Gardens, all of our books relate in some capacity to botany and horticulture,” Naumov said. “Our rare books contain many incredible examples of early European herbals and accounts of explorations and expeditions of plants. So, we want to preserve them mostly for educational value.”

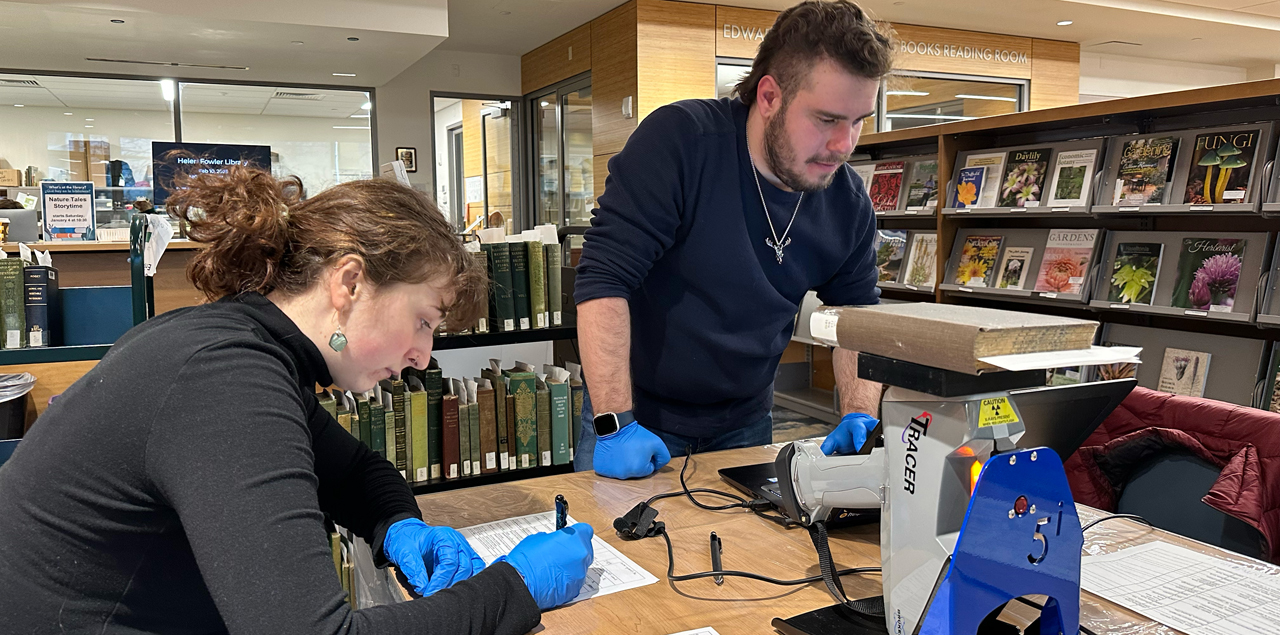

Happy to help, Hamilton enlisted her XRF Lab students, Alex Galloway, Aliyah Archer and Mackenzie McDaniel, and packed up the XRF to bring it to the Gardens’ library. There they scanned books dating back to the 1800s to see if they were contaminated with toxins including lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium.

“It’s amazing to use the knowledge we’re gaining to help people and not to do it for just the sake of knowledge. The professors here teach in applicable ways.”

Alex Galloway

“It was really fascinating handling these really old books and seeing all the illustrations of the books that were fairly niche gardening books,” said Anthropology senior Alex Galloway. “There were some that were native to New York, some from London, so it was fun to compare the differences in them.”

“This is the kind of thing people don’t often think about,” added Anthropology junior Aliyah Archer. “There are all types of contaminants in our daily items, so it was cool to see the evolution of what came up in the older books. The older the books were, the more toxins they had, which was our original hypothesis.”

The students spent a full day analyzing 93 volumes to determine if they had any “poison” in them and learned how to carefully handle the fragile manuscripts.

“A lot of what we found on the books was lead everywhere, which wasn’t surprising,” Galloway said. “We also saw a little bit of mercury, which shows up in red dyes, and arsenic, which shows up in green dyes.”

Galloway says the green they were looking for is called Sheele’s Green, a common dye that was used in making books back in the day. Out of the 93 books, only three had arsenic present.

“Arsenic usually accompanies these books from the 1800s that have a really brilliant jade green color,” Hamilton explains. “In a couple of the books, there were really beautifully colored monographs, and a lot of those were done by using these really toxic chemicals, so if you’re touching the arsenic books, there’s a good chance that you’re getting some of that coming off onto your skin, which is a hazard.”

Hamilton says there isn’t much that can be done to abate the arsenic on the books other than to contain it, which is what Naumov and her colleagues plan to do. The next step is to create custom enclosures for the books found with arsenic and label them as such so the public is aware of the need to handle them with custom care.

“Having them in individual boxes will also keep any potential dustings of the materials contained within their own little environments and not come into contact with other books in the collection, and we’ll require anyone handling them to wear gloves,” Naumov added.

While the work only lasted a day, Hamilton says it was a skill set the students will likely use once they begin their careers.

“Especially as anthropology majors, many of these students are looking into conservation, going into curation and museum work, so it’s really important to have that background knowledge of looking at an artifact, knowing how old it is, and checking to see if it has mercury or other toxins to be able to preserve the artifact,” Hamilton said.

In this case, Hamilton says, without knowing that the botany books needed extra and specific care, information in them about the history of herbal science and how it progressed could have been lost.

Which is exactly what intrigued Galloway most about this project.

“This is what anthropology is all about,” Galloway said. “Studying different cultures and how they reacted or did certain things differently, and that was clearly shown in the books. So, it was cool to be a part of something where you are working to preserve books and preserve these people’s perceptions. I appreciate an archivist’s job so much more now.”

Next Chapter

While she enjoyed examining the rare books with the XRF, Archer is interested in using the machine to conduct research in the public health industry. Beginning last year, Archer tested different types of everyday kitchen spices for heavy metals.

“I read different consumer reports about contamination in cinnamon, so I took samples of a bunch of different types of commonly used spices to see what I could find, and luckily I didn’t find anything major,” Archer said.

Using that data, Archer will now look at the element breakdown of the spices to see the nutritional value of each of them. Her goal is to get her master’s in public health after she graduates to interlace the human side of anthropology with the medical side of public health. She says her hands-on experience in using the XRF technology will greatly help her in the future.

“It’s pretty cool to have knowledge in this experience, and I’m really looking forward to continue building this niche skill,” Archer said. “I have a lot of different ideas of how the XRF could be used in the public health field for testing things for different contaminants, and there are probably potentials that we haven’t even thought of or discovered yet since it’s still relatively new in this field.”

Galloway is also interested in using his Anthropology degree to go into the public health industry. He plans to get his master’s in public health at UNC and focus his thesis on XRF data and community health centers for disadvantaged groups such as immigrants and refugees. He gained this passion through his hands-on coursework dealing with community outreach, including projects like The Poison Books testing at Denver Botanic Gardens.

“It’s amazing to use the knowledge we’re gaining to help people and not to do it for just the sake of knowledge. The professors here teach in applicable ways,” Galloway said. “It’s not just theoretical, the skills we learn are oriented towards gaining skills to get jobs and it’s nice to be around people that care about the community.”

Community members like Naumov are grateful UNC and its students are willing to share their knowledge and help with projects outside of campus.

“It was an absolute delight to work with Dr. Hamilton and the students,” Naumov said. “It was apparent that they were excited and interested not only in the testing itself but in the items they were testing as well.”

En el rincón de un laboratorio de Candelaria Hall hay una herramienta portátil parecida a una de esas pistolas de escáner de código de barras que utilizan los dependientes de los supermercados cuando vas a pagar en la caja. Sin embargo, esta herramienta se llama espectrómetro de fluorescencia de rayos X (XRF), y en lugar de descifrar el precio de una caja de cereales, el XRF determina qué elementos componen un artículo que está escaneando.

«La tecnología dispara un haz de rayos X de baja energía al elemento que nos interesa, golpeando alrededor de los electrones en los átomos, que luego envían una ráfaga de energía de vuelta al instrumento para ser medido», dijo la profesora asociada de Antropología Marian Hamilton, Ph.D..

Hamilton lleva utilizando el FRX en la UNC para sus investigaciones y cursos desde 2021. La tecnología es particularmente útil en su investigación de paleoecología, donde puede determinar la composición química en dientes de animales y fósiles óseos, revelando lo que comían los animales cuando estaban vivos.

Sin embargo, Hamilton afirma que la pequeña máquina puede detectar la mayoría de los elementos de la tabla periódica, lo que hace infinitas las aplicaciones del FRX.

«Lo mejor de todo es que cada elemento emite una firma energética única cuando sus átomos se mueven, así que si podemos medir cuántos trocitos de energía llamados fotones entran con cada una de estas intensidades energéticas, podemos saber qué elementos hay dentro de cualquier objeto», explica Hamilton.

Resulta que algunos de esos elementos pueden ser bastante peligrosos.

Uno de los usos más recientes del FRX en la UNC fue un proyecto relacionado con libros del siglo XVIII. Angela Naumov, directora de archivos y libros raros del Jardín Botánico de Denver, se puso en contacto con Hamilton para preguntarle si podían colaborar y utilizar la tecnología XRF para analizar la composición de los libros raros de la colección de la Biblioteca Helen Fowler del Jardín.

Naumov dijo que se enteraron de la existencia del Proyecto Libro Envenenado, que se centra en la identificación de pigmentos potencialmente tóxicos utilizados en componentes de encuadernación y en cómo manipular y almacenar colecciones tóxicas de forma más segura. Al no saber si alguno de los libros de su colección contenía estos elementos peligrosos, quiso hacer lo mismo con sus libros históricos.

«Como nuestra biblioteca forma parte del Jardín Botánico de Denver, todos nuestros libros están relacionados de algún modo con la botánica y la horticultura», explica Naumov. «Nuestros libros raros contienen muchos ejemplos increíbles de los primeros herbarios europeos y relatos de exploraciones y expediciones de plantas. Queremos conservarlos sobre todo por su valor educativo».

Feliz de ayudar, Hamilton reclutó a sus estudiantes del laboratorio de FRX, Alex Galloway, Aliyah Archer y Mackenzie McDaniel, y empaquetó el FRX para llevarlo a la biblioteca de los Jardines. Allí escanearon libros que datan del siglo XIX para ver si estaban contaminados con toxinas como plomo, arsénico, mercurio y cadmio.

«Es increíble utilizar los conocimientos que estamos adquiriendo para ayudar a la gente y no hacerlo por el mero hecho de saber. Los profesores de aquí enseñan de forma aplicable».

Alex Galloway

«Fue realmente fascinante manejar estos libros realmente antiguos y ver todas las ilustraciones de los libros que eran libros de jardinería bastante especializados», dijo el estudiante de último año de Antropología Alex Galloway. «Había algunos que eran originarios de Nueva York, otros de Londres, así que fue divertido comparar las diferencias entre ellos».

«Este es el tipo de cosas en las que la gente no suele pensar», añadió Aliyah Archer, estudiante de Antropología. «Hay todo tipo de contaminantes en nuestros objetos cotidianos, así que fue genial ver la evolución de lo que aparecía en los libros más antiguos. Cuanto más viejos eran los libros, más toxinas tenían, que era nuestra hipótesis original».

Los estudiantes pasaron un día entero analizando 93 volúmenes para determinar si contenían algún «veneno» y aprendieron a manipular con cuidado los frágiles manuscritos.

«Mucho de lo que encontramos en los libros era plomo por todas partes, lo cual no era sorprendente», dijo Galloway. «También vimos un poco de mercurio, que aparece en los tintes rojos, y arsénico, que aparece en los tintes verdes».

Galloway dice que el verde que buscaban se llama Verde de Sheele, un tinte común que se utilizaba en la fabricación de libros de antaño. De los 93 libros, sólo tres tenían arsénico.

«El arsénico suele acompañar a estos libros del siglo XIX que tienen un color verde jade realmente brillante», explica Hamilton. «En un par de los libros, había monografías de colores realmente hermosos, y muchos de ellos se hicieron utilizando estos productos químicos realmente tóxicos, por lo que si estás tocando los libros de arsénico, hay una buena probabilidad de que estés recibiendo algo de eso que se desprende en la piel, lo cual es un peligro».

Hamilton dice que no hay mucho que se pueda hacer para reducir el arsénico de los libros, aparte de contenerlo, que es lo que Naumov y sus colegas planean hacer. El siguiente paso es crear cajas a medida para los libros encontrados con arsénico y etiquetarlos como tales para que el público sea consciente de la necesidad de manipularlos con cuidado.

«Tenerlos en cajas individuales también mantendrá cualquier posible polvo de los materiales contenidos dentro de sus propios pequeños entornos y no entrarán en contacto con otros libros de la colección, y exigiremos que cualquier persona que los manipule lleve guantes», añadió Naumov.

Aunque el trabajo sólo duró un día, Hamilton dice que fue un conjunto de habilidades que los estudiantes probablemente utilizarán una vez que comiencen sus carreras.

«Especialmente como estudiantes de antropología, muchos de estos estudiantes están buscando en la conservación, entrar en la conservación y el trabajo del museo, por lo que es muy importante tener ese conocimiento de fondo de mirar a un artefacto, saber qué edad tiene, y comprobar para ver si tiene mercurio u otras toxinas para poder preservar el artefacto», dijo Hamilton.

En este caso, dice Hamilton, sin saber que los libros de botánica necesitaban un cuidado especial y específico, podría haberse perdido información sobre la historia de la herboristería y su evolución.

Eso es precisamente lo que más intriga a Galloway de este proyecto.

«En esto consiste la antropología», afirma Galloway. «Estudiar diferentes culturas y cómo reaccionaban o hacían ciertas cosas de forma diferente, y eso se veía claramente en los libros. Así que fue genial formar parte de algo en lo que trabajas para conservar libros y preservar las percepciones de estas personas. Ahora aprecio mucho más el trabajo de un archivero».

El siguiente capítulo

Aunque disfrutó examinando los libros raros con el FRX, Archer está interesada en utilizar la máquina para realizar investigaciones en el sector de la salud pública. A partir del año pasado, Archer analizó distintos tipos de especias de uso cotidiano en la cocina en busca de metales pesados.

«Leí diferentes informes de consumidores sobre la contaminación en la canela, así que tomé muestras de un montón de diferentes tipos de especias de uso común para ver qué podía encontrar, y por suerte no encontré nada importante», dijo Archer.

Con esos datos, Archer estudiará ahora el desglose de elementos de las especias para ver el valor nutricional de cada una de ellas. Su objetivo es obtener un máster en salud pública después de graduarse para entrelazar el lado humano de la antropología con el lado médico de la salud pública. Dice que su experiencia práctica en el uso de la tecnología XRF le será de gran ayuda en el futuro.

«Está muy bien tener esta experiencia y tengo muchas ganas de seguir desarrollando esta habilidad», afirma Archer. «Tengo un montón de ideas diferentes de cómo el XRF podría ser utilizado en el campo de la salud pública para probar cosas para diferentes contaminantes, y probablemente hay potenciales que ni siquiera hemos pensado o descubierto todavía, ya que todavía es relativamente nuevo en este campo.»

Galloway también está interesado en utilizar su licenciatura en Antropología para entrar en el sector de la salud pública. Tiene previsto hacer un máster en salud pública en la UNC y centrar su tesis en los datos de FRX y los centros de salud comunitarios para grupos desfavorecidos, como inmigrantes y refugiados. Adquirió esta pasión a través de su trabajo práctico en los cursos relacionados con la divulgación comunitaria, incluidos proyectos como las pruebas de The Poison Books en los Jardines Botánicos de Denver.

«Es increíble utilizar los conocimientos que estamos adquiriendo para ayudar a la gente y no hacerlo por el mero hecho de saber. Aquí los profesores enseñan de forma aplicable», afirma Galloway. «No es sólo teoría, los conocimientos que aprendemos están orientados a adquirir habilidades para conseguir trabajo y es agradable estar rodeado de gente que se preocupa por la comunidad».

Los miembros de la comunidad como Naumov agradecen que la UNC y sus estudiantes estén dispuestos a compartir sus conocimientos y ayudar en proyectos fuera del campus.

«Ha sido un auténtico placer trabajar con el Dr. Hamilton y los estudiantes», afirma Naumov. «Era evidente que estaban entusiasmados e interesados no sólo en las pruebas en sí, sino también en los elementos que estaban probando».