Harvesting Wheat

What do these photos tell you about how wheat was harvested?

A Wheat Field Near Montrose

This photo was taken in a wheat field near Montrose. The horses are pulling a grain binder. The binder cuts the wheat stems close to the ground and binds them in small bundles. The two girls visiting the field are sitting on bundles of wheat.

Photo: Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

More About This Topic

The first step in harvesting wheat was to cut the stalks of wheat. The stalks then were tied with pieces of twine into bundles called sheaves. In earlier times, farmers had to cut the wheat by hand with long-bladed scythes. Then they had to bind the sheaves by hand. By 1880, cutting and binding was done in one step with a horse-pulled grain binder. The binder allowed farmers to plant and harvest more wheat than before.

Their Own Words

"The women of the house had their share of the work. All the neighbors who helped with the harvest ate with the family in the house. In the very early days it took several days to thresh all a man’s grain. Usually there were up to twenty persons for the noon meal. Preparing meals for ten to twenty persons was no small task, especially without any conveniences at all. [For example] water had to be pumped from the cistern and carried into the house in buckets. Only a tea kettle and a reservoir were available for hot water. All used water had to be carried out again."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, "The Way It Was," The Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 110.

Bundles Or Shocks Of Wheat

This photo shows shocks of wheat standing in a field. Each shock contains several sheaves or bundles of wheat.

Photo: Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

After the grain binder cut and tied the wheat stalks into bundles, the farmer gathered the bundles into piles. These piles or shocks were left standing in the field until the farmer was ready to thresh the grain.

Their Own Words

"The odor of the new wheat, the dusty gray appearance of the men, the noise, the bustle, and all the men working together in the joy of the harvest was an experience that a child could never forget. At dusk the whistle blew, and everything stopped. Horses, tired and hungry, were released from the wagons, watered, fed, and bedded for the night in new straw. Then the men filed up to the cookhouse . . . and silently ate as only hard-working men can."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, "The Way It Was," The Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 109-110.

Loading Wheat Shocks On Wagon

The farmers in this photo are loading shocks of wheat onto a wagon. They are using pitchforks to lift the shocks.

Photo: Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

More About This Topic

The next step in harvesting wheat was to load the shocks onto a wagon and haul them to the threshing machine or separator.

Their Own Words

"The threshing crew went from farm to farm with a well-worked-out itinerary [schedule] and we knew about when to expect them. The cookhouse arrived first. . . . After the cookhouse arrived the men who had gathered the bundles [of wheat] from the fields drove in one by one, went directly to the new location, and started loading their racks."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, "The Way It Was," Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 108-09.

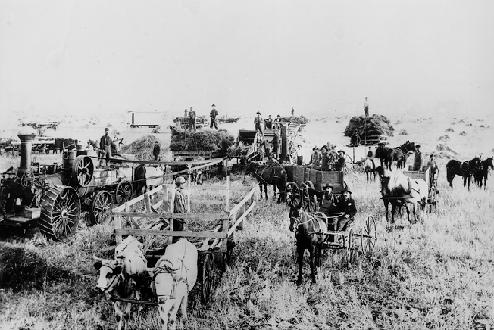

Threshing Wheat

This photo shows a steam engine, a threshing machine or separator, and farm wagons. Some of the wagons are loaded with shocks of wheat.

Photo: Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

The threshing machine separated grains of wheat from the wheat stalks. That is why it was also called a separator. The mechanism that did this was powered by a leather belt connected to the flywheel of a steam engine. In this photo the threshing machine or separator is in the rear-center. Beside it are wagons loaded with shocks of wheat. The steam engine is on the left.

Their Own Words

"The [wheat] separator was drawn into position; then the engine turned and backed for some distance. A heavy belt extended from the flywheel of the engine to the separator. This was a little tricky. The distance had to be exact, as the belt was long, in order to allow the wagons to approach and unload the bundle of grain into the maw of the separator. Soon we’d hear a long toot, the machinery would start, and thus began an exciting time for all."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, “The Way It Was,” Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 109.

Close Up Of Threshing Machine

This is a close-up photo of a threshing machine or separator. This machine separates the grains of wheat from the chaff or straw on which the grain grows.

Photo: Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

The men with pitchforks are feeding shocks of wheat into the separator. This was a dusty, dirty, and very hot job.

Their Own Words

"The very most exciting time of the whole year was threshing…. The water wagon would pull in and then we'd hear a whistle and the steam engine drawing the separator would come puffing up the road. Planks were usually placed across the bridge to reinforce it. The turn at the gate required some maneuvering as it was a sharp right angle and the road wasn't very wide…. Soon we'd hear a long toot, the machinery would start, and thus began an exciting time for all."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, “The Way It Was,” Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 108.

Bagging Wheat For Shipment

This photo shows another separator or threshing machine and the steam engine that powered it.

Photo: Denver Public Library, Western History Collection

More About This Topic

The thresher separates the grain from the wheat stalks. The grain comes out of the metal tube in the center of the machine and is collected in bags. The bags in front of the thresher are filled with wheat. The straw or empty wheat stalks is blown out of the machine into the pile on the right.

Their Own Words

"Grain pouring from the side of the separator emptied into sacks one bushel at a time. There were two spouts. While one sack was filling the other was taken off and loaded into a wagon backed up close. Barbara and I were allowed to ride back and forth on these wagons, and sometimes we would help pull the sacks back into the farther bins in the granary where a man stood to dump them through a hole in the floor."

Source: Hazel Webb Dalziel, "The Way It Was," The Colorado Magazine, 45 (Spring 1968): 108.