Trappers’ Rendezvous

A rendezvous was a trading fair that usually lasted several days. It is a French word for an appointment or meeting place. Missouri trader Captain William Ashley held the first trappers' rendezvous in 1825. Traders like Ashley brought trade goods--rifles, powder, traps, knives, tools, cloth, and beads--from St. Louis to the Rocky Mountains. The traders exchanged these items for the trappers' and Indians' beaver pelts. Each year the site of the rendezvous was usually in the center of trapping country. A rendezvous was held every summer between 1825 and 1840.

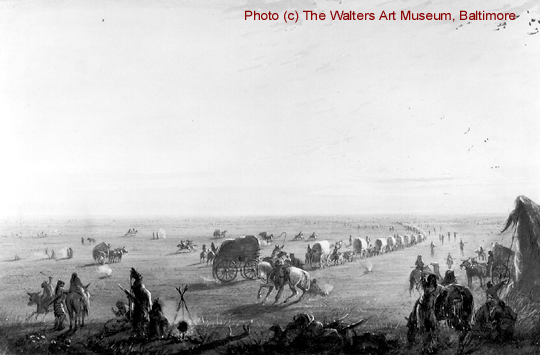

Breaking Camp At Sunrise

Alfred Miller titled this drawing "Breaking up Camp at sunrise." The wagons in this drawing are hauling goods for a rendezvous across the plains. When weather was good, the supply trains began each day very early. Miller described the start of the day as follows: "At four o'clock in the morning, it is the duty of the last man on guard to loosen the horses from their pickets, in order to range and feed. At daylight, everybody is up;--our [cooks] are busy with preparations for breakfast;--tents and lodges are collapsed, suddenly thrown down, wrapped up, and bundled into the wagons."

Source: The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, text for Plate 142.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.142)

More About This Topic

Before 1832, the supply trains most often consisted of pack animals. After that date, trains of two-wheel carts and wagons hauled trade items to the yearly rendezvous. In either case the traders traveled what they called the central route between Missouri and the Rocky Mountains. This route followed the course of the Platte River closely. Summer was the best time of the year to cross the plains, so supply trains usually began their trip in April or May. Early spring starts usually ensured that grass for the animals and water for all was available on the plains.

Their Own Words

"[At the start of the day] one of the strongest contrasts presents itself, and illustrates in a striking manner the difference between the white and red man. While all is activity and bustle with the Anglo-Saxon as if he feared the Rocky Mountains would not wait for him, the Indian lingers to the last moment around the camp fire. . . ."

Source: Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (1837) (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951): text for plate 142.

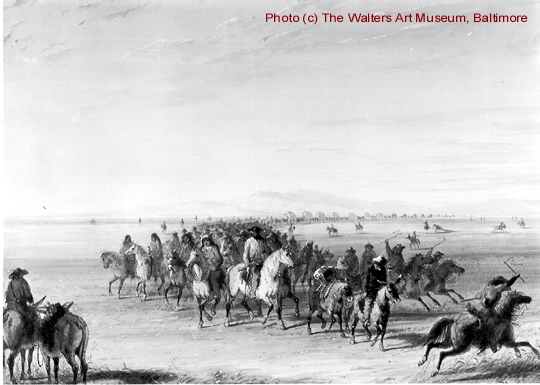

Caravan On The Move

Alfred Miller called this drawing "Caravan en route [on the way]." Supply trains were organized like an army. One person, usually the main trader, was in charge of the entire train. His word was law. As Miller described it: "The government of a band of this kind is somewhat [harsh], being composed of a [diverse] group of people from all sections, free and company trappers, traders, half-breeds, and Indians. Our leader was admirably [suited] for it, as he understood well the management of unruly spirits."

Source: The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, text for Plate 51.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (37.1940.51)

More About This Topic

The supply trains faced all kinds of problems along the way. For example, the plains were almost treeless, except along rivers and streams. The plains' climate in summertime is very dry. As a result, wagon wheels shrank and sometimes broke. It was impossible to replace broken wheel spokes with the wood that could be found on the plains. Wagon trains had to take along a supply of hard wood for making spokes.

Their Own Words

"In the first days our journey was straight west. The first day we marched over the broad Santa Fe road, beaten out by the caravans. Then leaving it to our left we took a narrow wagon road, established by former journeys to the Rocky Mountains, but often so indistinctly traced, that our leader at time lost it, and simply followed the general direction. Our way led through prairie with many undulating hills of good soil . . . On the prairie itself there is no wood."

Source: Frederick A. Wislizenus. A Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1839. (Glorietta, NM: The Rio Grande Press, 1969): 31.

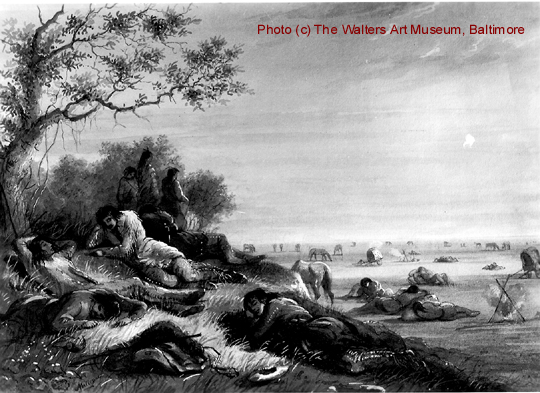

Noon Day Rest

Alfred Miller called this drawing "Noon-day Rest." Rendezvous supply trains usually began to travel each day at sunrise. The trains usually stopped around noon so the workers could rest and prepare a meal. The main reason for these rest periods was to let the animals that carried or pulled the goods rest. Each noon-day stop also avoided traveling during the hottest part of the day. The mid-day stops most often lasted several hours. As a result, travel to the rendezvous was slow. Most supply trains averaged only 10 to 15 miles per day.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.139)

More About This Topic

Crossing the plains with horses, mules, wagons and carts took a great deal of patience. The pace of travel was only as rapid as good care of the animals would allow. The pack animals needed to rest, to graze, and to water. Otherwise, the animals would not last through the entire journey. If the animals were lost, all was lost.

Their Own Words

"Every day at 12 o'clock the caravan halts, the horses are permitted to rest and feed, men receive their dinner, and then take a Siesta. . . . A guard is stationed of course, on the bluffs to prevent a surprise, and also to look after the horses, for,--Some must watch while others sleep,

Thus runs the world away."

Source: Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1956): Plate 139.

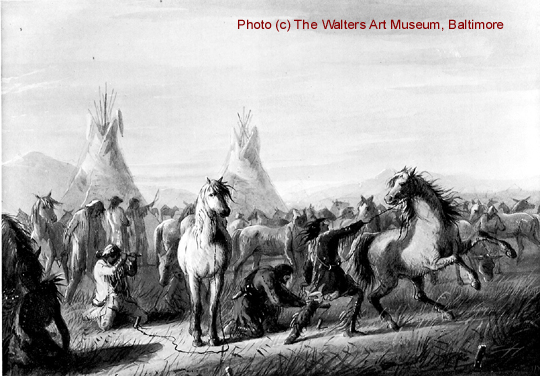

Picketing The Horses

Alfred Miller called this sketch "Picketing Horses." It shows how important the pack animals were to the train. After the commander of the supply train found a good camping place for the night, the most important activity was caring for the horses and mules. The second in command usually inspected the draft animals to see if they had sores on their backs. These sores were sometimes caused by packs rubbing on their backs all day. They were then watered and put out to graze. Only after these chores were completed did the people begin to prepare their own meals.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.178)

More About This Topic

Sometimes the supply train would travel until nearly sunset. At other times, the train would stop sooner if the commander found a good place to make camp. A good camping place usually had good water, plenty of grass, and an adequate supply of wood. On the plains, these places were usually along rivers or streams. Whatever the time the train stopped for the night, there was a lot of work to do. In addition to caring for the animals, the workers had to gather firewood, carry water for themselves, and begin to prepare the evening meal.

Their Own Words

"It is near sunset and the whole camp is very busy, the horses and mules have been driven in, and each man runs towards them as they come, secures his own horse, catches him by the lariat (a rope trailing on the ground from his neck), and leads him to a good bed of grass, where a picket is driven, and here he is secured for the night, the lariat permitting him to graze to the extent of a circle 25 feet in diameter, and all this is eaten down pretty close by morning."

Source: Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951): text for plate 178.

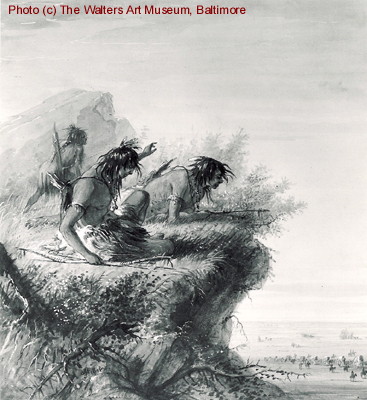

Dangers Along The Trail

Alfred Miller called this drawing "Pawnee Indians watching the caravan." Miller said that "of all the Indian tribes I think the Pawnees gave us the most trouble." On the plains, the Pawnee were regarded as especially hostile and dangerous to travelers. Even so, the trappers regarded Indians of most plains tribes with caution and suspicion. These Indians usually viewed the supply train's stock of animal as especially prized targets for theft.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.44)

More About This Topic

In traveling to rendezvous, the traders and trappers encountered many different Indian tribes. Some of these tribes were openly hostile to the traders and trappers most of the time. On the plains, one of these tribes was the Pawnee. Even when the traders and trappers encountered friendly tribes, they did not trust them very far. They were constantly on alert to protect their goods and animals from these Indians.

Their Own Words

"Of all the Indian tribes I think the Pawnees gave us the most trouble, and were (of all) to be most zealously guarded against. We knew that the Blackfeet were our deadly enemies, forewarned here was to be forearmed. Now the Pawnees pretended amity [friendship] , and were a species of 'confidence Men'. . . Whether they were within the Camp or in our vicinity it was [important] to put a double guard over the horses. Then when we were [on the move] we were continually under their [watchful eyes], and we knew it."

Source: Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951): text for plate 44.

The Lost "Green Horn"

Alfred Miller called this drawing "The Lost 'Green-Horn." Trappers applied the term "greenhorn" to people new to the trade of trapping. Greenhorns lacked experience in terms of the environment, of wild animals, and of Indians. Their lack of experience and knowledge often put these people at great risk.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.141)

More About This Topic

The greenhorns were often assigned to the easiest tasks. At first, the greenhorns served as cooks and camp-keepers, attended the animals, and were assigned night watch over the camps. If they accomplished these tasks well, they might then be assigned more skillful tasks. But greenhorns had to prove themselves before they were given additional responsibilities.

Their Own Words

"On reaching the Buffalo District, one of our young men began to be ambitious, and although it was his first journey, boasted continually of what he would do in hunting Buffalo if permitted. This was John (our cook), he was an Englishman . . . Our Captain, when any one boasted, put them to the test, so a day was given to John and he started off early alone [to hunt buffalo]. [After being gone two days] one of the [search] parties brought in the wanderer--crest-fallen and nearly starved;--he was met with a storm of ridicule and roasted on every side by the Trappers."

Source: Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951): text for plate 150.

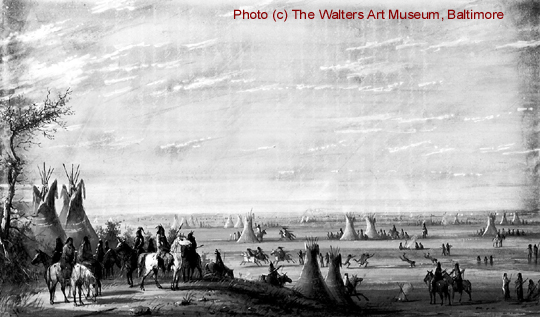

The Trappers' Rendezvous

Alfred Miller called this drawing "Rendezvous." It shows a scene at the rendezvous of 1837, which Miller attended. As Miller described the scene: "At certain specified times during the year, the American Fur Company appoint a 'Rendezvous' at particular localities (selecting the most available spots) for the purpose of trading with Indians and Trappers, and here they congregate from all quarters. The first day is devoted to 'High Jinks" . . . in which feasting, drinking, and gambling form prominent parts."

Source: The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, text for Plate 110.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.159)

More About This Topic

After months of traveling, the supply train finally arrived at the place for the rendezvous. These places were usually selected a year in advance, so everyone would know where to go. The ideal location for a rendezvous was a wide mountain valley. The location needed good grass and water for the animals, wood for fuel, and ample game for food. However, no single location could support all the trappers, traders, Indians, and their animals that came together for these trade fairs. The rendezvous had many campsites clustered around a central market place. These small camps were moved often as water and grass were exhausted.

Their Own Words

"Our next objective point was the upper Green River valley . . . [where] we found traces of whites and Indians, that had journeyed ahead of us through this region a short time before, probably to the rendezvous, which takes place yearly about this time in the neighborhood of the Green River. As our destination was the same, though our leader did not know precisely what place had been chosen for it this year, some of our men were sent out for information. . . . The journey which we had made from the border of Missouri, according to our rough estimates, was near 1,200 miles."

Source: Frederick A. Wislizenus. A Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1839. (Glorietta, NM: The Rio Grande Press, 1969): 83, 84, 86..

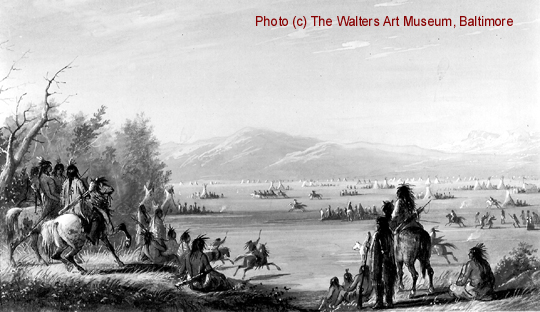

Scene At Rendezvous

Alfred Jacob Miller titled the drawing (to the right) "Scene at 'Rendezvous.'" He described the scene as follows: "A large body of Indians, Traders, and Trappers are here congregated, and the view seen from a bluff is pleasing and animated. In the middle distance a race is being run . . . Ball playing . . . and other games are largely indulged in, and the Company make it a point to encourage the Indians in these sports to divert their minds from mischief. . . ."

Source: The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, text for Plate 175.

Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (AJM, 37.1940.175)

More About This Topic

The rendezvous served two purposes: celebration and business. For the trappers, the former was very important. For the traders, the latter was definitely most important. For their furs, the hired or company trappers received supplies for the following trapping season, perhaps some luxuries such as tobacco and alcohol. The trappers were generally paid poorly for their labors and the risks they ran. Prices for the goods brought from St. Louis were high compared to the prices of beaver pelts.

Their Own Words

"A good hunter can take an average of 120 [beaver] skins in a year . . . worth in Boston about $1,000. [The trappers] can be hired for about $400 payable in goods at an average of 600 per [cent] profit."

Source: Nathaniel Wyeth, quoted in David Wishart, The Fur Trade of the American West, 1807-1840 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979): 197-198.