Like many, I have an Apple Watch. Each morning, it nudges me to exercise. My Peloton also does this, digitally encouraging me to achieve fitness goals. I also often go to Starbucks. While there, I collect virtual stars—rewards in its mobile app.

We already live in a gamified world, where systems are designed to be game-like, offering rewards along the way. Gamification is nothing new, of course; it’s been around for nearly a decade. Gamification was defined by the Pew Research Center back in 2012 as “interactive online design that plays on people’s competitive instincts and often incorporates the use of rewards to drive action.” Gamification elements can include digital badges, leaderboards, progress bars, and the ability to level up. And it is everywhere these days, from fitness bands to massive online open courses (MOOCs), such as Coursera and Khan Academy, to financial apps, like Robin Hood, Zelle, and Venmo.

Meaningful Gamification

Many gamification systems can seem like sticker economies, more carrot than stick. As research suggests, extrinsic motivators, like stickers, badges, gold stars, and other reward systems, can actually demotivate some learners. But good gamification can be much more nuanced. Game design professor Scott Nicholson proposed meaningful gamification, “the use of gameful and playful layers to help a user find personal connections that motivate engagement with a specific context for long-term change.”

Nicholson uses a syllabus and course analogy to describe meaningful gamification. The syllabus, he writes, is like a good gamification system in that it provides the structure of a meaningful reward system. The coursework that takes place throughout the semester is the game, where students are afforded playful opportunities to learn.

Sid Meier, the famed designer of games and simulations like the Civilization series, was once asked to define games. His pithy reply was that good games are simply a “series of interesting choices.”

Coursework can be game-like as well when presented as a “series of interesting choices.” In my ed tech courses, I think about popular games with “Creative Modes,” like Fortnite and Minecraft. As it happens, there is a classroom version, Minecraft: Education Edition, which has lots of downloadable maps and lesson plans. Back in 2020, I worked with the Denver Writing Project to bring a set of writing prompts to Minecraft, which I wrote about here in my Edutopia blog: https://edut.to/3tlHkOZ.

Based on Minecraft’s approach, students in my courses learn about ed tech tools in “Survival Mode,” which may engage them in listening to podcasts or playing educational escape room games. Then the coursework switches to Creative Mode, project-based learning opportunities where students make podcasts and design their own escape room games. This process of playing then making can create conditions for meaningful learning, much like a good game. Once this is in place, I start gamifying in my syllabus and on Canvas.

The Science Behind Meaningful Gamification

Meaningful gamification should support self-determination theory (SDT), the innate human need to feel a sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2018). In the context of coursework, autonomy is when students are engendered with a sense of being in control, driving the learning experience in a learning environment. Relatedness is the social feeling of connectedness we feel with others (friends, colleagues, peers) (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2018). Competence describes how we feel when new skills or concepts are just within our grasp (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990/ 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2018).

Many people play games because it meets our needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Ryan & Deci, 2018). Games afford autonomy through player agency, “the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decision and choices” (Murray, 2017, p. 159). Good games keep players in a flow channel, where skill and difficulty increase just enough to make players feel competent (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990/2008; Ryan & Deci, 2018). Games are also social, as many feature communities where players converge to share experiences.

From Gamification to Game-Like Learning

In my new book, Gaming SEL: Games as Transformational to Social and Emotional Learning, I share how students can develop social and emotional learning skills, such as goal-setting, empathy, perspective-taking, and teamwork in learner-driven environments. One approach is to use choice boards, a strategy that many educators use as a step toward supporting self-determination. Often written as a menu of options that students can take to demonstrate learning, choice boards vary. They can be made digitally using hyperlinks on shared Google or Microsoft documents, or educators can remix from free online templates online, too, including options from SlidesMania. Choice can manifest in physical classrooms as well, with learning stations geared toward specific learning outcomes.

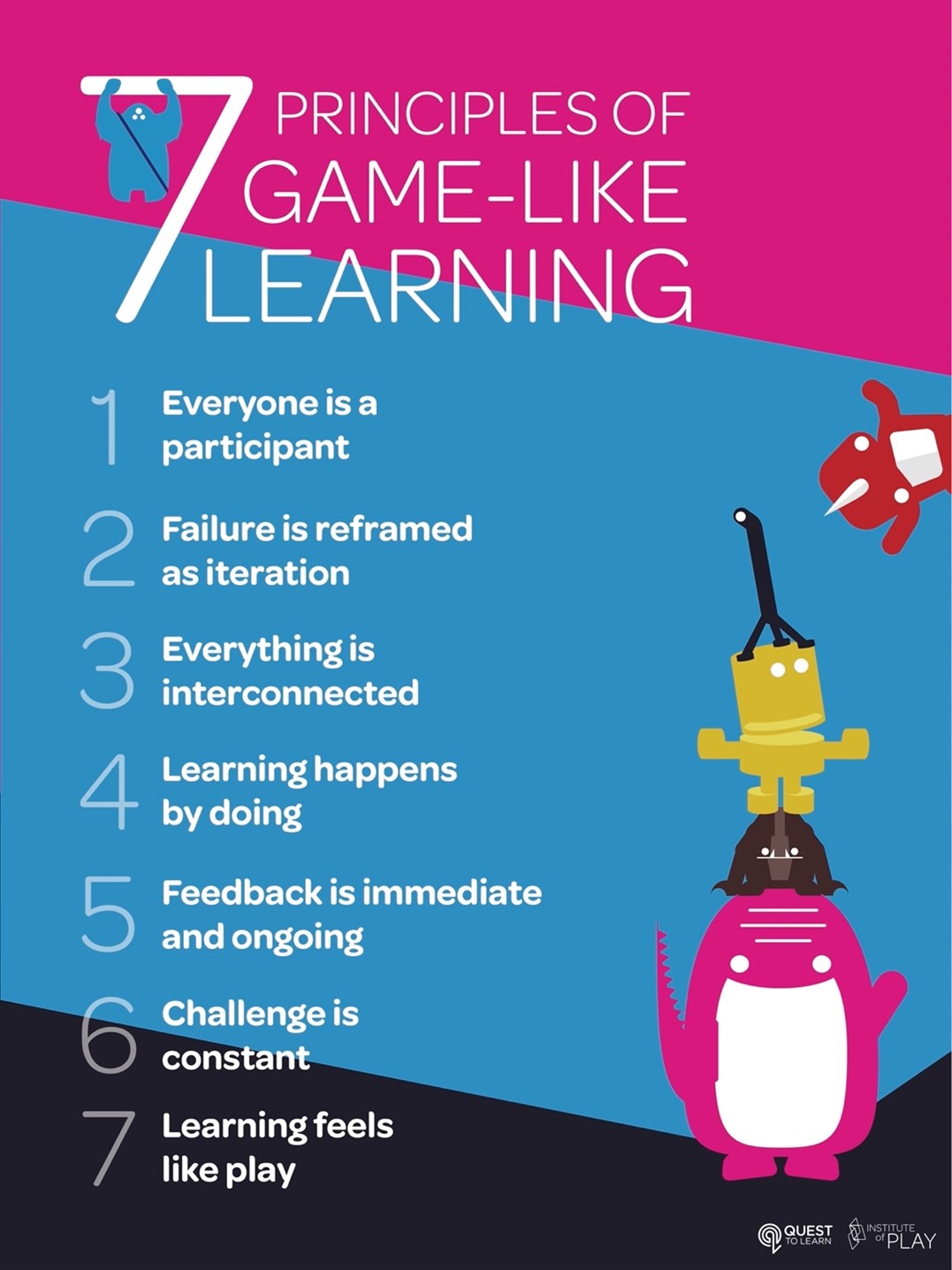

These days, many classrooms have gamified formative assessments, such as game show-style quizzes that can both engage and assess. Kahoot is a common example, as is the newer Gimkit. In my courses, we play Socratic Smackdown, a live gamified Socratic debate game. To learn more, check out the free resources from the Institute of Play, now part of the University of California, Irvine’s Connected Learning Alliance: https://clalliance.org/institute-of-play/. In addition to Socratic Smackdown, the work of the Institute of Play includes its Game-Like Learning Principles.

I was inspired by Lee Sheldon, professor and author of The Multiplayer Classroom: Designing Coursework as a Game. First published back in 2011, it is now in its second edition. In this book, Sheldon describes in detail how he created syllabi that turned his courses from traditional and passive learning experiences to interactive and “multiplayer,” like a game.

At the university level, also see GradeCraft, a gamified learning management system (LMS) from researchers at the University of Michigan. For even more, check out the resources on my webpage, including my book, Gamify Your Classroom, and blog posts on Edutopia.

Game on! \o/

References and Further Reading

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. (Original work published 1990)

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self- determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Kohn, A. (1999). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton Mifflin.

Farber, M. (2021). Gaming SEL: Games as Transformational to Social and Emotional Learning. Peter Lang.

Farber, M. (2017). Gamify your classroom: A field guide to game-based learning – Revised edition. Peter Lang.

Murray, J. H. (2017). Hamlet on the holodeck: The future of narrative in cyberspace. MIT Press. Nicholson, S. (2014). A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (eds.), Gamification in education and business. (pp. 1–20). Springer.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self- determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Sheldon, L. (2020). The multiplayer classroom: Designing coursework as a game (2nd edition). CRC Press.