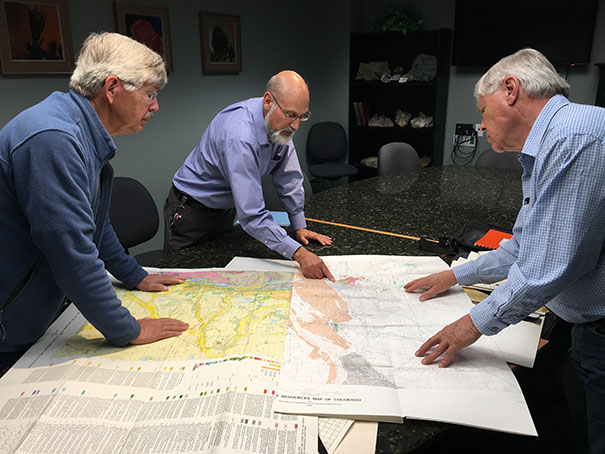

From left: Bill Nesse, Bill Hoyt and Raymond Pierson review drilling logs, maps and photos of the site that Raymond has kept all these years.

Raymond Pierson smelled opportunity.

It took only a few whiffs during a UNC field trip in 1980 to convince him to act.

His UNC professors, Lee Shropshire and Bill Nesse, made a habit of taking budding geologists to a site outside of Loveland that Pierson's class was visiting that day in 1980. The outcropping there was significant for a couple of reasons. Namely, it exposed the Niobrara Formation, a mineral-rich deposit in the Denver basin stretching across the northeast corner of Colorado and into parts of neighboring states.

Students could literally smell the hydrocarbons from the exposed section known as the Codell at the base of the Niobrara.

Pierson did more than take notes about the sediment and large fossils he observed that day. An experienced oil and gas worker before he arrived at UNC, the undergraduate at the time took samples and then decided to write a research paper for a special study under Professor Nesse.

The study would become the catalyst for the big project Pierson imagined. Just six months after he submitted it to Professor Nesse on Dec. 9, 1980, it would become a signature part of his career.

------------

Pierson came to UNC from New Mexico. There, he cut his teeth in the oil and gas business after three tours in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam serving in the Navy.

Gazing at the barren expanse of land where the pumps were working in New Mexico, Pierson puzzled over how geologists knew where to explore underground.

"It was the most amazing thing I came across in my life," Pierson said. "I asked myself at the time, 'how can they possibly figure out where to drill? They can't see all the way down there.'"

A colleague urged him to take a geology class. He did and became more intrigued. His University of New Mexico instructor, sensing his desire to learn more, recommended he further his studies at UNC.

Nesse, now retired, recalls Pierson as a "delightful" student with undying curiosity. He routinely peppered Nesse with questions. Pierson was passionate about learning as much as he could about geology so he could return, armed with an education, to the oil and gas business.

--------------

It took some convincing, and some fits and starts, but upon graduation from UNC Pierson eventually persuaded a company to take a core sample to analyze the subsurface.

One of the petrophysicists Pierson worked with before the core sample was taken asked him what they should call the project file for record-keeping purposes. When Pierson shrugged, his colleague suggested "Raymond's Folly," quipping "there ain't nothing there, and I'm not sure why you're pursuing this."

His remark couldn't have been more wrong. The core sample would reveal the presence of hydrocarbons in an area that Pierson's well log analysis found equaled 1,728 square miles (the size of eight townships long and six townships wide).

"Today, there are thousands of producing oil and gas wells in the Codell," Pierson said. "This reservoir has produced billions of dollars of product and has helped Weld County (responsible for 89 percent of the state's oil production in 2015) to be a very prosperous region of Colorado."

Academic papers have been written about the discovery, and his peers have credited him as the geologist who discovered the Codell Sandstone Oil and Gas production. Pierson laments, however, that those papers omit citing UNC as the birthplace since his study originated as part of the special study under Nesse.

When Pierson earned his Earth-Sciences-Geology degree in 1980, UNC didn't have a specific program aimed at developing geologists for the oil and gas industry. Today, UNC offers a master's degree program in Environmental Geosciences, which provides specialized training in applied sciences related to water, minerals, energy and environmental management.

"There are still big discoveries yet to be made," Pierson says. "The students today are going to be the ones making those discoveries."

More Stories

-

‘In It for the Long Haul,’ Alumna and District 6 Educator Wins Presidential Teaching Award

Egresada de UNC y educadora del Distrito 6 gana medalla presidencial de enseñanza

-

UNC's 2025 Honored Alumni Awardees and Celebration

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Athletic Training Program Evolves to Meet Market Demand

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Honored Alumni Nominations Open: Help Us Recognize Outstanding Alumni

Este artículo no está en español.