By 2060, around two-thirds of the world’s population will live in cities and will need sustainable drinking water. We can provide clean drinking water to urban areas if we keep nearby ecosystems healthy.

UNC Assistant Professor in the Environmental and Sustainability Studies program Chelsie Romulo, Ph.D., recently had her research on investments for watershed services published in the journal Nature Communications.

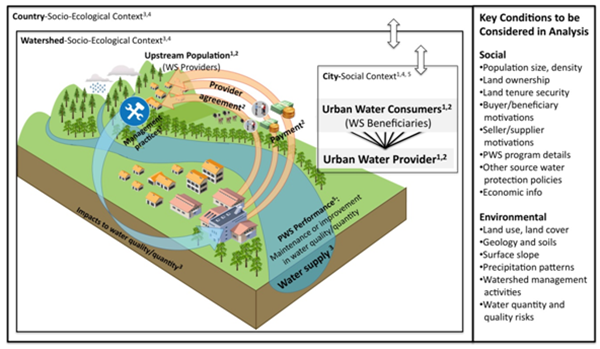

Simply put, a watershed is the area of land that drains into a common body of water, such as into the mouth of a bay. Watersheds can provide a natural service, which are things that nature provides to humans like water filtration. The investments in watershed services programs are activities that connect rural areas to cities. A city invests in supporting rural areas’ abilities to provide watershed services to them — in this case, clean drinking water.

Romulo and her team reviewed data collected by The Nature Conservancy using a machine-learning algorithm to better understand the variables that impact the placement of these investments for watershed services.

In this podcast, UNC Creative Content Producer Katie Corder sat down with Romulo as

she explains the importance of these programs, how she conducted her research and

future steps in using the model to locate more potential areas for these investments

for watershed services.

Read along with the full transcript of the podcast:

So just to start things off, can you describe your published research?

This paper that we just published was the culmination of a very large, interdisciplinary project looking at programs called payments for watershed services, or investments for watershed services, that link cities to rural watersheds and try to distribute funds from those cities to promote good watershed maintenance.

The idea being that if people who are drinking water in a city want to have clean water then the best thing to do would be to actually pay for the people living in watersheds to do things like maintain riparian buffers and have a clean watershed.

So, I’ve never heard of … it’s IWS, right, the acronym?

Yea, they’re sometime called investment in watershed services, payment for watershed services or water funds. In our paper, we used the term ‘investments’ because sometimes those investments are not monetary.

A really good example is New York City. They have one of these programs where they actually have an outreach program, so people who are paid by the city go out and they work with farmers on how to maintain their properties so that there’s not non-point source pollution, or run off, into the streams. So, investments we felt like encompassed a broader range of programs that fit this need.

So, the whole talk about basically farmers, so it comes from rural areas over to more urbanized areas, correct?

A couple of reasons why we are interested in this work is that by 2060, about two-thirds of the world’s population are going to be living in cities. So, this is a big change from even just 100 years ago when most people lived close to the resources, so now, we have to transport things like food, water and energy to where the people are living. And so, we want to make better connections between the people who are using resources, and the people in communities who live in the places where those resources are produced.

Another reason why we are interested in this project is that The Nature Conservancy, which is a global, non-governmental, or NGO, organization and nonprofit, has been working as an intermediary to help set up these programs. They facilitate the discussions between cities and urban communities, and so, in their work, they started collecting a lot of data regarding what could be important for where these programs can be established or be successful, but they didn’t know what to do with all of that data and it was getting kind of overwhelming.

And this is a broader question in the scientific community regarding the idea of big data: there’s just so much data out there, but not all of that data is important, and not all of it is relatively important when you consider all of the available data. We’re actually working with TNC, The Nature Conservancy, in order to figure out how they can use this data effectively to be better targeted in where they try to establish these programs.

I’ve heard big data is a huge issue, and it can be crazy overwhelming with information overload, so how have you and your team been going through that data?

What we started with was just looking into the theoretical literature, and the case study literature, and so, there are a lot of theories about what could be important for the establishment in one of these programs, and so, we want to start with what the theorists say is important.

We collected data for as much as those different things as we could, which ended up being 70-something variables that, through a few different statistical analyses, we whittled down into just 17 that we compared.

The process that we used is a type of machine-learning process, and so, we put all the data together and we basically tell an algorithm to start dividing the data based on different variables. Given the variables being tested, which ones are more important relative to the other variables? So, the output is given a bunch of different segments of data and a bunch of different groupings of variables, these are the things that tend to be more correlated with the presence or absence of a payments for watershed program.

Can you give an example of the variables that you worked with or found?

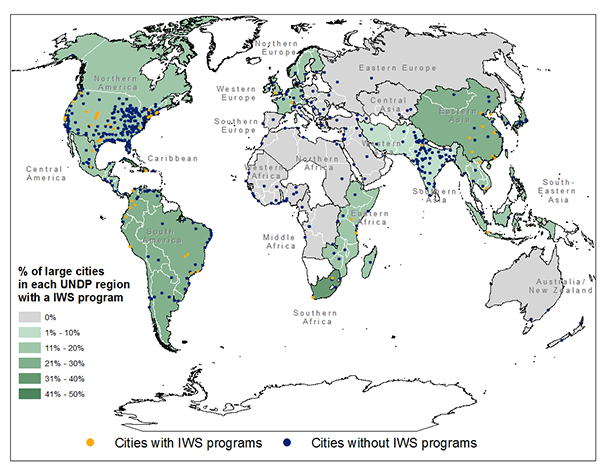

One of the first things that we put together was this giant map of where programs currently exist, and if you’re looking at our paper that would be figure 2 (see below). In that figure 2, you can see that there’s definitely parts of the world where those programs are more common, and other parts of the world where they’re less common, and some parts of the world that don’t have any of these programs at all, so that was really interesting to look at. Once we had that database put together, we could start looking at the theoretical literature and case study literature to aggregate our different variables.

Some of the variables that we considered were things like how big is the watershed? How far is it from the city? And one thing that was interesting when we were going through all of the literature is that we would find some papers that said things like, “If you have too many people then that would be a barrier,” and then another piece of literature said, “If you had too few people then that would be a variable.” And so, for some of these variables, it looks like there would be an optimal size of maybe a threshold that would be important in establishing one of these programs, so we wanted to investigate that a little bit further.

Where did these IWS programs, where are their origins in the world, where did they start, how fast did they grow and how common are they?

We need to value the services that ecosystems do for us in a really direct way, so ecosystems, plants, natural environmental cycles do things like clean our air, clean our water, and so we don’t pay for those services in any real sense. In trying to figure out how we could actually pay for those services so that we don’t inadvertently degrade them, the idea of payments of ecosystem service came about, so these programs have been around for a couple of decades, but they’ve really been gaining traction in the past few years.

There is an organization called Forest Trends that actually tracks these types of programs around the world. Forest Trends does a lot of different things, but their program that looks at this is called Ecosystem Marketplace, and they have an article about Denver Water. One of the things that Denver Water does is, so if you are a person who receives water from Denver Water, then you pay for your water bill each month, and a portion of that money goes to things like planting trees. And so, we know that in a watershed if you have a good, healthy ecosystem that includes trees, those trees help to clean the water, so the water that’s like running off from rain or snow melt, and so, Denver Water invests in trees in the watershed so that people in Denver can drink clean water.

So, you say these things are picking up speed, where are they most popular? Are they most popular in America, and if so, do you think this is going to become a commonality around society as years go by?

One of the things that we found is that these programs are much more common when a large portion of the watershed is being used for agriculture. And that makes sense because in places that have agriculture, there is concern about things like run-off and how the land is being maintained, so there is potential in those locations to do one of these programs and improve the watershed. These programs are less common when the watershed is already protected, and that makes sense because if your watershed is already a national park or there’s some watersheds in the Pacific Northwest that are owned by the water utility companies, so they maintain and preserve the environment.

As we’re looking at how drinking water is being used, it’s also dependent on where your drinking water comes from. So, if your drinking water comes from an aquafer, or like in India there’s a couple large cities that use desalination, there’s no watershed associated so the program’s less likely there. We also found that these programs tend to be in places with certain types of elevation and in places where countries are investing in conservation.

What we’ve done with our findings is given it to The Nature Conservancy so they can look at these things since we know that these programs are more likely to be located in a place where the watershed is largely in agriculture, they can look at different watersheds in the world and say, “Okay, where are these watersheds that have a lot of agriculture, but they don’t have a program?” Then we can say, “Okay, do they have a different program to maintain their watershed? And if they don’t, then would that be a good candidate?” That’s the place where The Nature Conservancy can come in and say, “We can function as a mediator and as a connector between your urban drinking water users and your rural suppliers of water.”

So, it’s almost like using natural resources and keeping them up to grade in order to make the resources we need to live being present, being maintained and everything like that, so it’s using natural resources for our own benefit.

Absolutely, and that’s exactly what these programs are trying to do. The term for the things that nature does for us is eco-system services — the beneficial things that nature does on its own like cleaning water and cleaning air — and so the idea is that the more that we can promote and maintain and maybe even restore nature’s ability to do these things then we don’t have to do these things artificially.

So, let’s say your average citizen living in a city learns about this, why should he/she care?

The so-what question is really critical, and there’s two responses to the so-what question:

- The first is that I hope everybody is concerned about access to clean drinking water. So, these programs are established specifically to provide people, especially those people who live in urban areas, with clean drinking water. I mentioned before that over two-thirds of the world’s population is going to be living in a city in not very many years, so we need to have systems in place that are able to provide cities with clean drinking water and do it in a sustainable method, so there’s that aspect.

- The other aspect is the applicability of what we’re doing for The Nature Conservancy, and so, The Nature Conservancy, before our project came along, was using a lot of data to try to figure out where are those places that are likely have a project be successful. The first step in understanding where a project might be successful is to establish what are the commonalities between the locations that already have these projects, and we’ve done that first step. So we provided them with a way to look at the data they were already collecting in a more efficient way, and so hopefully this will allow them to have targeted work so that they’re only working in places that are likely to have a program or likely to commit to a program, that means for a nonprofit that people are donating money to they’re more efficient with their money.

Can you describe future steps or future research be it involving this topic or another topic?

You’ll see that the distribution of cities with these programs is not equal around the world. There are large cities all over the world, and in some places like North America and even South America, the percentage of those large cities that have one of these programs is higher than a lot of other places. Australia doesn’t have any; most of Africa doesn’t have any, except for the eastern coast and sub-Saharan Africa. India has a ton of large cities but very few programs. China actually has a lot of these payments for watershed services programs. So, for next steps we want to get into that regional level information and see why is it that some places are more likely to have them compared to other places, what are they doing?

How did you get to where you are now? How did you get involved with watershed and the eco-services and everything like that?

I became very interested in how people make decisions about the way that they manage or interact with our natural resources, so I wanted to get more into the realm of what’s called human dimensions of natural resource management, and I am a type of scientist who is really interested in methodologies. And so, I really love aggregating evidence and looking at it in different ways or combining it with other evidence to try to answer big-picture questions about how we can manage these resources sustainably.

Well, excellent, thank you so much!

Thank you!

More Stories

-

Daniel Garza’s Journey from Platteville, Colorado, to Stellenbosch, South Africa

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Crafting a Home Field Experience

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Doctoral Candidate Tackles Social Issues Using Data Science

Este artículo no está en español.

-

Bridging the Gap Between High School and College: Frontiers of Science Institute

Este artículo no está en español.