Burma Musings

Young Buddhist Nuns: Myanmar (aka Burma)

Shwedagon Pagoda: Yangon, Myanmar

Burma/Myanmar (#7)

10-14-06

Today I turn 57. I sat on my deck this morning and watched the sun rise over the Bay of Bengal as we make our way to Chennai (the old Madras), India where we dock tomorrow morning. With only two days between ports, my reflections on Burma/Myanmar seem fragmentary, elusive…

The entry into Burma was not as spectacular as either our approach into Vietnam nor Hong Kong. But it is a country which while 90% devout Buddhist, has been under a military regime for 46 years. There is no underlying ideology to this military regime except power coupled with the will to control its own people.

The population of Burma (which the military junta re-named Myanmar—perhaps to mystify the outside world—successfully, I might add) must be challenged daily with the surreal balancing of the nonviolence of their religion with the realities of a war-torn, totalitarian state. We are docked about an hour from what used to be known as Rangoon, now Yangon. When we enter into and out of the area, we are required to sign in and out, “for security.” According to our guide (who spoke in a lowered voice in a crowded tea room), there is one radio and one television station both controlled by the government—they only broadcast good news—, and people are so afraid to check out certain web sites, that they self-censor so as to keep themselves out of trouble. Singing the wrong song, writing a poem, could land one in jail.

MI (Military Intelligence) are everywhere, even though you can't see them. No one in a local tea shop will talk to you because you might be MI. MI dress as Buddhist monks, common folk, vendors, and spy on the people of Burma. A culture of fear permeates the country; villages can be conscripted, and made to work on roads and buildings. When I approached a road crew of men and women in longyis with baskets of rocks on their head, I was warned away by armed police.

Estimates range from 25% to 50 % of common citizens who have been arrested, tortured, and (killed) or returned to civilian life (now ostracized) on any suspicion that they may have criticized (and therefore are labeled as revolutionaries) the current government. Fear of imprisonment, torture, and being ostracized create this ubiquitous culture of fear in Burma. Many question why we [S@S] are here—clearly our money contributes to the coffers of the military. But I believe that the more people (sophisticated students in our case) who learn about Burma, the more difference we can make…

Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of the “George Washington” of Burma and Nobel Peace Prize winner of 1999 has been on and off under house arrest since 1989. She was not able to see her British husband before he died of cancer and she has not seen her children in 10 years. Her house is guarded by arm guards—you cannot get within even a block of it. Photos are only allowed in certain areas—military buildings, guards, police, or soldiers cannot be photographed. And yet people were friendly; shop keepers were anxious to ply their goods, and I even talked to an antiquities dealer who was working on a Ph.D. in anthropology!

I guess in a less ominous way, Burma is a weird country. When we passed into Burmese waters, we set our clocks back one-half hour. While Burma is not the only country whose time zone is on the half hour (Newfoundland, Tehran, Adelaide and Darwin, Australia also are half hour off of GMT; [Katmandu is on the forty-five minute!]), it is nonetheless unique. Furthermore, there are eight days in the week (this has to do with astrology). Wednesday is divided into 2 days: Wednesday morning and Wednesday afternoon, each with its own animal sign (actually, a tusked elephant for the morning and an un-tusked for the afternoon). A former military leader (Ne Win) resigned (unexpectedly) on 8-8-88 because he believed it was an auspicious day to do so (numerology/astrology again); a student protest which eventually led to the deaths of thousands also took place at 8:08 a.m. on 8-8-88.

The Burmese drive on the right hand side of the road, but the steering wheel is on the right hand side too. A few years ago, a general was cut off by a motorcycle, so motorcycles are forbidden. What this means is that the poor (who make up most of the country) have no access to private transportation.

To use the word crowded to describe the public buses and trucks does not do justice to the scene. The roads and infrastructure are a mess: the first night in Yangon it rained heavily, and the streets were flooded: folks (including me) were walking through calf length water; in the confusion, my wallet was stolen from my backpack. Fortunately because this is a cash-only economy, I was not carrying my id, and so lost only about $40 in cash. There is not a single ATM machine in the country, and I did not see a bank in all of my travels.

Other than that, it’s a charming country. Women and men wear longyis, a sarong-type garment, and shorts and tank tops are not allowed in any religious areas (which occupy a great deal of the city). Thanaka, a yellow-bark ground up with a mortar and pestle into a paste is worn by most women and some men and children who wear it (like make-up) on their face and body. The effect is, well, different. I went to a market in a small town, and it felt like I had retreated a century back in time. The vendors were selling wild duck blood (I asked), as well as other unrecognizable food items including betel nut—the red juice is spattered on sidewalks, pathways, roads. Children pointed at me and stared, waking their mothers from their afternoon naps. I’m sure I was not the first westerner these children have seen as there is quite a bit of tourism in the city, but I musty have been unusual enough to pique their interest.

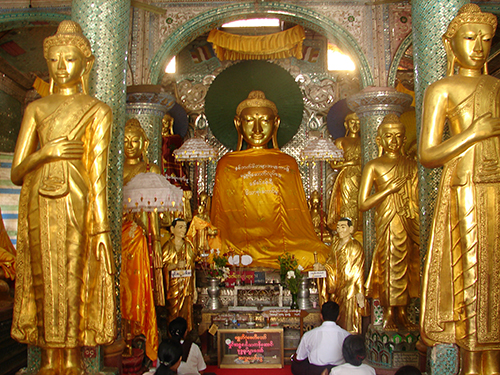

The Shwedagon Pagoda is a golden pagoda that marks the center of the city. It has over 4500 images of the Buddha and 1000 pagodas; it is gaudy and yet lovely in its own way. It sits in the center of the city on Singuttara Hill and is 2500 years old. It houses relics of the Buddha including 8 strands of his hair encased in gold and jewels. There are 5448 diamonds (including a 76 carat diamond at the top which you cannot see), 2317 rubies, sapphires, and other gems, 1065 solid gold bells—all of this in a country where people are impoverished. Each "altar" is regularly re-gilded with gold paint—a way of gaining "merit" for a better reincarnation.

While there, I (accidentally) met a young Buddhist monk, Agga, who I ended up spending an eight hour day with, visiting the local Buddhist shrines in the city and talking about everything from Myanmar politics (in the privacy of a park area where we could not be overheard) to the benefits of meditation. We struggled a bit with the language barrier, but his English (which he wanted to practice) was remarkably good, once I learned to listen. He is 23 years old (reminded me a lot of Jeff) and was a novice between the ages of 10 and 20. At the age of 20 he decided that this way of life suited him, and so he went through the ceremony to become a full fledged monk. He was dressed in the dark red robes of Myanmar monks and we looked a bit incongruous as we walked a good six miles around the city, he keeping a pretty good pace. These are the experiences which do not come up often in semester at sea unless you simply go off on your own.

I also went to a Buddhist “novificiation” ceremony. All young men are expected to become Buddhist monks, even if it is only for 7 days (their families want the ceremony), and so I attended one. It was fascinating, but perhaps not so much as the "feeding" ceremony where I was able to interact (superficially) with young monks and nuns—most of whom are in monasteries or nunneries because it is the only place where they can get an education and food. But I am obsessed with the terror that many of these young girls may be sold into prostitution, or young boys brain-washed as soldiers...

This country is an enigma. I keep thinking I am missing something—that there are things that I should process but haven’t. Maybe had I left the city, I’d have had a different experience. I seemed to encounter a lot of people scared to talk about the government (I never brought up the topic, but that is how they explained their feelings), a lot of poverty, and thousands of the nearly 500,000 monks who wander the city with their “begging bowls” requesting food or money for their meals as well as their missionary movements.

We arrive in India tomorrow—miss you all, love, sally