One of the oldest cultural centers in the nation, the spirit of Marcus Garvey Cultural Center remains stronger than ever, celebrating and championing Black culture and history.

At the corner of 10th Avenue and 20th Street stands a house that has been part of UNC’s history since the 1950s. Although the Marcus Garvey Cultural Center (MGCC) was officially dedicated in 1983, the inception of its core values dates back more than 70 years. Since it opened its doors, ‘the Garvey,’ as it is known to the UNC community, has gone through many changes, but one thing has remained constant: Its mission to provide a safe gathering space, critical resources and a home-away-from-home for UNC’s Black community.

The Marcus Garvey Cultural Center. Photo by Woody Myers

As the Garvey celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, the community reflects the people who made the center possible and honors its profound impact on the UNC community.

In the 1950s and 1960s, UNC, then Colorado State College (CSC), was home to a small number of Black students — among them, Les Franklin, a graduate of Palmer High School in Colorado Springs. Franklin came to UNC in 1958 to study Business, excited to attend college, especially at the same college where a few of his friends enrolled before him.

“I knew some kids who went up to Colorado State [College] before me… they seemed to have a good time, so I thought I ought to give it a shot.” Franklin said.

Franklin moved into Hays Hall, across the street from the baseball field at Jackson Field) and settled into campus life. He was one of approximately 10 Black students, and although small in number they created their own spaces and community on the predominately white campus.

“We called ourselves the ‘Ebony Omegas’ back then,” Franklin shares. “We did everything together and tried to make the best of the situation.”

The Ebony Omegas often met at the Bru-Inn, the old student union located in Gray Hall. They were never a formal club, but rather a community of young men who found comfort in each other’s presence.

At the time, racism was pervasive at colleges across the country, and Franklin experienced his share of racism while pursuing his education. In 1961, he was dating a young white woman who, at the time, was president of one of the Panhellenic sororities on campus.

“I took her to a concert on campus,” Franklin says, “I went to pick her up from the sorority house [where she lived]. When I arrived, the other girls in the house would not speak to me.”

Arriving at the concert in Gray Gym, he was heckled by people in the stands. Franklin and his girlfriend did their best to ignore the harassing behaviors and enjoy their night. But a few days after the concert, targeted racist graffiti appeared on campus.

Franklin recalls feeling hurt but was not surprised by the graffiti. Interracial relationships were considered taboo, regardless of the fact that Colorado legalized interracial marriage in 1957.

Franklin graduated from Colorado State College in 1962 and went on to launch a successful career in business.

In the coming years, the university began to make important changes and strides in creating a multicultural campus. In 1969, the Afro-American Studies program, now Africana Studies program, was established and remains one of the oldest in the nation. This was a critical step toward recognizing Black history as American history and illuminated Black culture and history within the academic community. It was also instrumental in the Garvey’s creation.

The Afro-American Studies program attracted more Black American scholars to UNC, and among them was Professor Robert Dillingham, who was hired in 1977 as a lecturer and served as faculty advisor for the Black Student Union on campus. In 1979, he became the chair of the Afro-American Studies program.

By this time UNC had approximately 300 Black students and Greeley saw a steady increase in its Black population. However, this spurred an increase in racially motivated incidents and necessitated the need for more support to Black students and community members.

Dillingham, along with UNC’s Black faculty and staff, joined forces with Black Student Union president Neil Williams (B.S. ’83) and other BSU leaders to improve support systems, recruitment programs and career preparation initiatives for Black students.

“We were very concerned that Black students were not getting the right guidance for their education and career,” says Dillingham. “We wanted the university to form a committee that would look into these concerns.”

As a result, the UNC Committee on Black Student Concerns was formed in 1982 and, after four months, drafted a report highlighting institutional racism and barriers directly affecting the Afro-American Studies department, Black students on campus and the larger campus and Greeley communities.

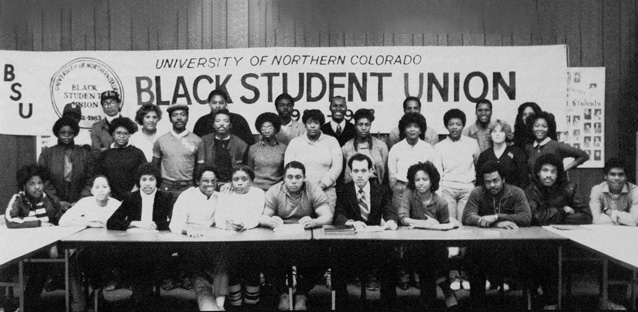

1982-83 Black Student Union, photo courtesy UNC Archives.

These efforts led to the creation of the Marcus Garvey Cultural Center.

“The MGCC was designed to assist [with] the academic enrichment skills of Black students through tutorial programs, guidance counseling, career counseling and personal counseling addressing institutional racism,” said Dillingham.

“We wanted to develop a career services and cooperative education component to help students get field experience internships, interview techniques, [access to a database for job opportunities [and] increase graduate school placements.”

With a student-focused mission in mind, the Marcus Garvey Cultural Center was dedicated on February 1, 1983, with Bobby Seale — the co-founder of the Black Panther Party — giving the keynote address. However, the celebration was short-lived when just a day after the dedication, the center was defaced and vandalized with a sign featuring the imagery and values of the Ku Klux Klan left on the front door.

Clearly, there was still much work to be done.

Since its founding, MGCC has worked tirelessly to bridge gaps in student need and has become an integral part of campus. It serves as a safe and welcoming home and resource for Black students, celebrating and championing Black culture, milestones and history for the campus community.

UNC’s first cultural center, the Garvey has focused on retaining Black students and providing them with access to career panels and guidance, networking opportunities and academic success resources.

Through the years, the Garvey has supported thousands of Black students, faculty and staff. From celebrating national victories for Black Americans to mourning the lives illuminated through Black Lives Matter, the Garvey has been a haven on UNC’s campus and for the community.

Alumna Monique Atkinson (B.A. ’11, M.A. ’17) recalls the Garvey being a place of shared celebration when Barack Obama became the first Black U.S. president.

“I voted for the first time for the first Black President in 2008,” Atkinson recalled. “Campus was quiet once they announced Barack Obama was the president. The residence halls, classes, Holmes [Hall]... everything and everyone was silent. However, at the Garvey, the silence was met with celebration, smiles, laughter and excitement. The Garvey provided a space for Black students to celebrate ourselves in being a part of something so great.”

That celebration extended to student connections and service within the community. Alumna Alexis McCowan (B.A. ’19) recalls the many times that the Garvey facilitated student service within the city of Greeley.

“[We] would volunteer to serve food to those facing homelessness in the Greeley area. The staff, all girls that year, [would] sing and dance as we prepared food in the small kitchen. Our giggles echoed down the stairways as we carried food into the cars for transportation,” she remembers.

“There was always joy in that place, but especially on those days, because despite what factors may have been impacting our lives academically, physically or emotionally, we always had the Garvey.”

Creating spaces for Black campus and community members to simply “be” and feel at peace became a success and pride point of the center’s creation.

“The Garvey was the first place on campus where I felt I could truly be myself outside of my dorm room.” says Shanelle Robinson (B.A. ’14), “I loved the Garvey so much I ended up working there… it quickly became my second home.”

New Black staff members at UNC also found space for company and support, sharing in the hardships of job relocation, brainstorming ideas for initiatives in their departments and discussing ways to handle difficult situations. “I have gained a lot of support in my role on campus, especially when things are hard,” shared Jala Randolph, a current UNC staff member. “I know the Garvey is a space that will walk alongside me as an advocate.”

janine m. weaver-douglas*, Ed.D., director of the Marcus Garvey Cultural Center, believes that the work happening today remains strongly aligned with the Center’s founding mission.

“We strive to be a place where Black students find challenge, and opportunity, where they can propel themselves into their own bright, beautiful futures,” weaver-douglas shares. “We aim to make those pathways permanent, while building new bridges of partnership and outreach for those we will serve in the future.”

Last summer, in collaboration with the City of Greeley and with generous support from PDC Energy, the Garvey hosted the university’s first-ever, community-wide Juneteenth celebration, now a federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. The event drew hundreds of people from across Greeley and the campus community, more than double the anticipated attendance numbers. The celebration included more than 25 community and campus vendor and partner booths, which contributed material goods and money directly to Black makers, doers and creators.

On February 4, 2023, the UNC community coalesced around the Garvey — this time for its 40th anniversary — with an open house and public reception. Alumni, staff, faculty and Greeley community members came together to celebrate the many accomplishments and milestones that happened over the last 40 years. Professor Dillingham was among those who attended the event.

“It is an honor to be able to be here all these years later,” Dillingham said at the event. “It feels good.”

Today, UNC has four cultural centers and four resource centers and institutes designed to empower students to reach their academic, personal and professional aspirations. Although each center has a separate mission, the entwined values and dedication to making UNC a diverse, welcoming and inclusive community for everyone is evident.

weaver-douglas said she is thrilled to celebrate the Garvey’s 40th anniversary and

acknowledges

the work of the many directors that have come before her.

“The Garvey benefits from a long, storied legacy of active and engaged stewardship and leadership that worked to create passageways for Black students, staff and faculty to find community, relationships and development while at UNC. We are proud to be entering our 40th year.” UNC

By Shadae Mallory ’17

*janine m. weaver-douglas has requested that her name be recognized through the use of lowercase letters.