Holding High Expectations

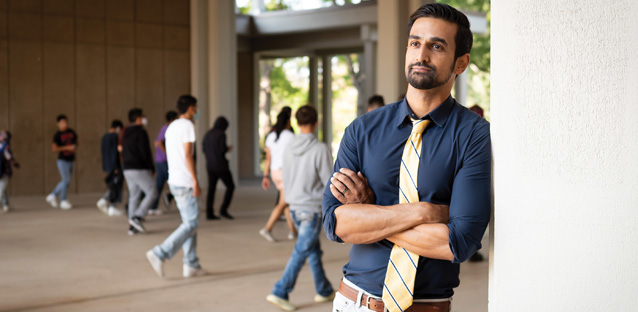

UNC Trustee Shashwata Prateek Dutta BS 08, EdLD, believes in the importance of education as a driver of social mobility — something he’s experienced in his own journey to success.

It was 2008, three years after Hurricane Katrina’s waters reshaped the city of New Orleans. Prateek Dutta had recently graduated from the University of Northern Colorado with a degree in Political Science, joined Teach for America, and was facing a classroom of sixth graders. He had arrived in that classroom after his own journey through the education system with a sense of understanding and wanting to make a difference.

Teach for America focuses on educational equity with a cadre of leaders who commit to teaching for two years.

He and his colleagues worked hard to instill in students the importance of college but found that while many students went on to attend, many didn’t, and that was something he wanted to change.

“I’m passionate about college as a means to the end goal of empowering people and making sure they have the tools to go up the economic ladder. I feel education is the best means to do that, or the fastest way to do that.”

It’s a belief rooted in his life experiences.

Dutta’s parents grew up in East Pakistan, which is now Bangladesh. “At that time, the United Nations called it the poorest place in the world,” Dutta says. “My dad’s dream was to come to the United States to study, which is what happened. He got a student visa and went to school in Boston.”

His father brought his mother to Boston, and Dutta and his sister were born there. His father, who’d earned his PhD in Economics, was working as a professor, but language barriers became an obstacle to teaching. With no job, and unable to pay the bills, the family made the painful decision to leave the U.S. and move to Kolkata, India, where they remained until Dutta was about eight years old.

“At that time, my parents decided they wanted to give the American dream one more chance. So, they basically looked at a map of the United States and said, ‘Colorado looks like a place for a fresh start.’ They got two suitcases, changed their currency — the rupees changed to about $40 — and came to Denver,” Dutta says.

Because he didn’t speak English, Dutta was placed in an English as a Second Language (ESL) classroom where most students spoke Spanish. “Teachers had a hard time interacting with me for a bulk of my elementary and middle school,” he remembers.

Gaps in learning became chasms. By high school he was far behind academically, with grades that he knew would make entry into a four-year university impossible. He started applying to community colleges, but says UNC was his dream school.

“I met with (UNC’s) director of admissions and he told me my grades and test scores didn’t cut it, but they’d see what they could do.”

Dutta applied, and was accepted on the condition he take summer classes.

“UNC was the only university that took a chance on me, and so I am eternally grateful. It changed the trajectory of my life because without being accepted into UNC, I honestly don’t know what I would’ve done,” he says.

Getting to UNC was just part of the battle.

“I was so far behind. Everything took so much longer for me. It’s not a sob story at all, just the reality. My favorite place in the entire campus was Michener Library. I loved it. I used to go to Starbucks, get a massive cup of coffee, and from 7 p.m. to midnight, I would stay in that library and study every night.”

Dutta says UNC faculty trustee and Professor of History Fritz Fischer helped him succeed.

“He was an incredible force for my life. He made teaching fun and engaging, and I think one of the reasons I applied to Teach for America was because of his class. I was in his class on the Vietnam War, and I remember thinking ‘how can he make something so complicated, so engaging?’”

At the time, Dutta wasn’t sure what he wanted his career to be, but based on his experience in school, he knew he wanted to help students who were overlooked or marginalized.

“I applied to Teach for America and I got accepted, and then I was placed in New Orleans. That’s how I got started teaching.”

In New Orleans, Dutta began to feel his efforts were bringing change for the short term, but not for the long term, and as much as he loved working with the students there, he decided to take his own education a step further.

“I realized no matter how much work I did in the classroom, there were some other powerful societal forces that kept putting students in a different trajectory. I realized I needed more skills and a better understanding of policy and politics to really make a difference. That’s why I went to grad school.”

He was accepted into a doctoral program at Harvard University focusing on Educational leadership.

“I honestly struggled to graduate high school 10 years before I got accepted to Harvard. And so obviously there’s a lot of feeling of, ‘do I belong?’ I did well there, but I didn’t like it as much as UNC. I never felt that sense of home that UNC brings. I got my degree and I’m happy I got it, but to compare that to my UNC experience is just night and day,” Dutta says. “I will put our UNC professors and our students against Harvard students and faculty any day of the week. But without question, I had a better experience at UNC than I did at Harvard.”

He completed his doctorate, and felt that instead of working within the system, he could do more outside the system, advocating for change. He returned to Denver and became the Colorado policy director for Democrats for Education Reform (DFER).

“Democrats for Education Reform was created because the Democratic party has historically been pushing for equity on a whole host of issues, but when it comes to education, sometimes the party has defended the status quo. Our organization works to move both politics and policy forward to ensure all students receive a high-quality education.”

For Dutta, his years as a student, a teacher and an advocate have shown him the importance of having high expectations.

“I know what it feels like when teachers and schools have low expectations for certain groups of students. When you hold students to high standards, they’ll always meet them.”

Low expectations, he asserts, are a veiled form of racism. The positive impact of

holding students to high expectations is something he saw first-hand as a teacher

working with low-income students in New Orleans as they coped with significant hardships

in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. When taught with high expectations, they succeeded.

The opportunity to succeed in school did not come to Dutta until he became a student

at UNC, and he brings that experience — coupled with teaching, graduate work, and

his work for DFER — to a new role at UNC.

In January 2020, Colorado Governor Jared Polis appointed Dutta to a three-year term as a trustee at UNC. He is attuned to concerns about inequity in higher education in addition to his focus on K-12 education.

“Higher education is not absolved from inequity. We’ve done a really good job of decreasing high school dropout rates across the country. But what we have not done is decrease college dropouts. The majority of low-income students that go into college, drop out; the majority of Black students and Latino students that go to college drop out. And they have nothing but debt after they’ve dropped out. It’s unacceptable. And we need to do something about that. All higher education institutions, including UNC,” Dutta says.

As a trustee, he sees UNC facing multiple challenges — including student retention and graduation rates. And while he has high expectations for students, he also has high expectations for his alma mater and its ability to address those challenges.

“We must increase our enrollment and retention while closing the attainment equity gap in graduation and retention. Our new strategic plan — Rowing, Not Drifting — creates a roadmap on how to overcome these challenges and make UNC stronger. Most importantly, the strategic plan ensures our university is more student-centered and has a more coherent student support system,” he says. “I think we have a great opportunity to take students that might come from underprivileged backgrounds and really propel them into the middle and upper class. UNC’s mission, I would say, is to be an engine of equity. And to really be a driver of social mobility.”

–Debbie Pitner Moors

Social Mobility and Higher Education Rankings

As many prospective college students can tell you, universities and colleges are ranked in many different ways — student-teacher ratios, the size of the school’s endowment, cost of tuition and even the number of students turned away.

One way to measure a school’s ability to address equity and help students climb the economic ladder is the Social Mobility Index (SMI). According to the SMI website, “A high SMI ranking means that a college is contributing in a responsible way to solving the dangerous problem of declining economic mobility in our country.”

The SMI rankings for colleges and universities are computed from five variables: published tuition, percent of student body whose family incomes are below $48K (slightly below the US median), graduation rate, median salary approximately five years after graduation, and the size of the school’s endowment.

Out of the nearly 1,500 colleges and universities ranked by SMI, UNC is first in Colorado (ahead of Colorado State University-Pueblo and Colorado State University-Fort Collins), and 286th overall.

What does that mean for students? “If a student wants to pursue academics in an institution that models awareness and civic responsibility, the SMI can provide a valuable guide,” the SMI organization says. “In the end, the greatest returns to self from work, academic or otherwise, come from delivering benefits to family, nation, and our world. Families and students who understand this and want to move up efficiently to a position of social and economic influence in our country will gravitate to high SMI schools.”