Colorado Indians Tour One

This virtual field trip is a tour of the Ute Indian Museum. The museum is located in Montrose, Colorado.

It is devoted to the history and culture of the Ute tribes and to the life of Ute Chief Ouray and his wife Chipeta. The Colorado Historical Society runs the museum.

This virtual tour can give you only a glimpse of the contents and richness of the Ute Indian Museum. The virtual tour will show you some of the items exhibited here. It will provide you with as much information about those items as space allows. We urge you to visit the museum whenever you are close by.

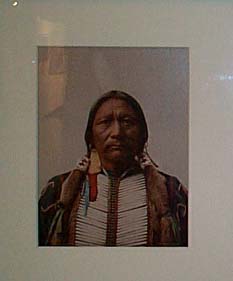

Ute Chief Ouray

"Ouray, leader of the eastern Utah bands of the Utes, was selected by the United States government to be the Chief of the Ute Nation (as the seven bands of Utes were officially named). Half Tabeguache Ute and half Apache, Ouray led the Utes in a time of social and political change during which his people were uprooted and forced into resettlement. He was a man of peace in a time of war between Utes and whites. One of the greatest of Ute leaders, Ouray directed his energies to solving the problems of his people during and after the loss of lands, and he traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with presidents and congressmen in hopes of peaceful solutions to war."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

"Settling on a 500-acre homestead at this site [at what is now the Ute Indian Museum] after the establishment of the 1868 reservation boundaries, Ouray died in Ignacio, Colorado, in 1880. In the traditional manner, his body was wrapped in a blanket, laid in a rocky spot and covered with branches and rocks. Forty-four years later, his remains were gathered from the initial resting place and reburied in the tribal cemetery in Ignacio. His beloved wife Chipeta lies on the land of the homestead, on the [Ute Indian] Museum grounds."

Ute Chief Ouray's Shirt

This shirt is a beaded buckskin shirt in maroon, yellow, dark blue on a white background.

It has a fringed flap opening at the front and back. It also has about 12 inches of

fringe at the bottom.

Chief Ouray's wife Chipeta made this shirt for him to wear on his trip to Washington,

D.C., to negotiate a treaty with the federal government. When Ouray died in 1880,

Chipeta sent the shirt to Carl Schurz, a friend of Ouray's who was involved in the

treaty negotiation. Schurz's family eventually donated the shirt to the Museum of

the American Indian Heye Foundation, which, in turn, donated it to the Colorado Historical

Society.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Chief Ouray's Artifact Case

The mug in this display case of some of Chief Ouray's artifacts was given to Ouray

by United States President U. S. Grant (Grant was President from 1869-1877).The mug

is made of silver. It has a handle and has a capital "O" engraved on the side. Later,

Ouray presented this mug to J. E. Gardner whose son Frank donated the object to the

Colorado Historical Society in 1937.

Another interesting object in this display case is the knife that belonged to Chief

Ouray. The knife has a bone handle and steel blade. It is decorated with brass circles.

Gordon Kimball, of Ouray, Colorado, later owned the knife. At his death, William Rathmell

became the owner and his son Henry donated it to the Colorado Historical Society in

1958.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

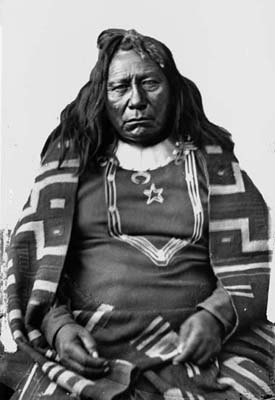

Chipeta

"Born a Kiowa Apache but raised as a Tabeguache Ute, Chipeta became Ouray's second wife in 1859 when she was sixteen and he twenty-six. As the wife of this Ute diplomat, Chipeta lived in two worlds: that of her family and Ute heritage, and that of the ever-closer whites. On trips with her husband to Washington, D.C., she held on to her Ute ways and did not try to adapt to white culture, but she charmed eastern [United States] society."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

"The couple lived in a house that the United States government provided for them near Montrose, the surrounding land extending to include this [Ute Indian] Museum acreage. But after Ouray's death, and for the remaining forty-four years of her life, Chipeta lived with her people and shared their joys and hardships. When the Utes were expelled from Colorado in 1880, Chipeta was among them, seeing the last of the land her husband had tried so hard to save for his people. Following her death, her body was returned to the homestead she shared with Ouray. Her monument lies just north of the [Ute Indian] museum building."

Source: Text from Ute Indian Museum

Chipeta's Artifact Case

We apparently don't know very much about some of the items you see in Chipeta's artifact display case. This is simply to point out that the "provenience" (a big word that essentially means the story and authenticity of a specific artifact or document) of artifacts like these is very important. Without knowing the story behind such artifacts, we have difficulty dating the items and knowing whether they are authentic (that is, whether they are, in fact, what is claimed for them).

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Who Are The Utes?

The Ute Name:

"Known to other groups [of Indians] by many names, the Utes referred to themselves

as Nuche, "the people." In the southwestern part of their homeland, the Utes were

called "Deer Hunting Men" by the Zuni and the "Mountain People" by other Pueblo communities.

Out on the plains to the east, they were known as the "Black People" to the Cheyenne

because of their dark skin color, and as the "Rabbit Skin Robes" to the Omaha and

Ponca peoples. The name by which we now know them came from the Spanish terms Yutas,

Uticas or Utacus."

"The Utes are the longest continuous residents of Colorado. While it is not known exactly when the first of their people came from the north and west, they had lived in their mountain and plateau homeland for centuries by the time the Spanish arrived in the 1500's. Their original territory stretched across portions of the Colorado Plateau, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. In 1800, just before the influx of Euro American traders, miners and settlers, the Utes occupied an estimated 140,000 square miles of territory. Their nomadic existence was based on hunting large and small game and gathering the grasses, roots, berries and fruits native to the area."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

Ute History

"For over 1,000 years, the Utes crossed western America's great mountains and high plateaus, hunting as they went and confident that so long as they stayed true to their traditions their lives would remain unchanged. Their origins are largely unknown, but since their arrival they have occupied the western half of present Colorado. The Utes were divided into seven main bands, but for the most part traveled in smaller clans, the better to find game and feed the people. Membership in the groups changed as individuals moved from band to band. During the warm half of the year, groups spread across the broad landscape, but gathered in winter and early spring to socialize and participate in ceremonies and events such as the Bear Dance."

"The acquisition of the horse, as well as the adoption of elements of Plains Indian culture such as the tipi, profoundly changed Ute life. Mounted on their sturdy ponies, the men could venture far afield in conflict, search of food or trade. Women set up tipis, raised and taught children, gathered and cooked food, prepared hides and made baskets, household goods and clothing."

"More changes came with the coming of the whites. Pushed onto ever smaller sections

of land, the Utes found it increasingly difficult to support themselves. Without the

free movement necessary to follow herds of elk, deer and buffalo, they were threatened

with starvation. Also, the hordes of whites who increasingly entered the high country

in search of gold and silver saw the Utes as a menace to nineteenth century notions

of progress and the march of civilization."

"Unlike many Plains tribes, the Utes experienced little warfare in relations with the United States government, preferring instead, with Ouray and other leaders at the forefront, to negotiate peaceful settlements to conflict. By 1880, the Utes were forced from the state--except for the three southern bands who now live on the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain reservations in southwestern Colorado."

The Utes Today

"The seven Ute bands now reside on three reservations. In Colorado, the Mouache and

Capote bands comprise the Southern Ute Tribe with headquarters in Ignacio, and the

Weeminuche band is settled around Towaoc as the Ute Mountain Tribe. The Northern Utes--the

Tabeguache, Grand, Yampa and Uintah bands--live on the Uintah-Ouray reservation surrounding

Fort Duchesne, Utah."

"Today's Utes are separated from their old traditions by more than a century of struggle to save their culture and yet survive as a people in a non-Indian world. The three tribes have never abandoned their resistance to the forced change of lifestyle and the loss of their homelands, and have continued the fight, often in the courtroom, to keep their traditions alive. All have developed a base of industry to support tribal economic security and provide income for tribal members, including agriculture, mining, water and gas leases, and tourism, among other industries. In spite of hardship, the people have retained their humor, their pride and their commitment to their heritage."

The Coming of the Horse

"The Utes were among the first Indian peoples to obtain horses in the centuries after

the arrival of the Spanish, and they quickly became admired and feared for their skill

as horsemen. The Utes were now able to travel greater distances than ever before:

this changed their lifestyle by opening up access to the plains, where buffalo herds

provided a new source of food. Increased contact with Plains tribes brought both conflict

and the opportunity to trade goods and ideas."

Source: Text from the Ute Indian Museum

Diorama of Ute Village

This diorama depicts a Ute village sometime after about 1500 (one way to tell is the presence of horses in the village). After the Utes acquired horses, they were better able to hunt buffalo on the plains. In their new contacts with plains tribes, they learned to make tipis from buffalo hides.

If you look closely at the photo, you will see an Ute man at the right of the diorama.

He is stripping bark from an aspen tree limb with a stone knife. He is making a tipi

pole.

The several women in this part of the diorama are setting up a tipi. They set up

all the poles first, then they raised a pole with the hide cover attached. The cover

was brought around to meet at the doorway and the edges of the cover were pegged to

the ground. The woman in the center of the unfinished tipi is making a fire pit. Smoke

from the fire escaped from a flap left open at the top of the tipi. In the center

is a man unloading buffalo meat, brought into camp on a travois. Behind the tipi is

a fire and tripod rack on which the meat was dried. The dried meat was ground with

berries and mix with fat to make pemmican (this is what the woman in the finished

tipi is doing). In the far background, women are scraping buffalo hides. The hides

were scraped, dried, dressed, and used for many things, including saddles, tipi covers,

blankets, clothing, and carrying cases (parfleches). In the left foreground, a woman

appears to be working on some sort of craft (clothing or beadwork) while a child looks

on. A baby is in a cradle board which is hanging from a tree trunk.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

As you move through this virtual tour of the Ute Indian Museum (or when you visit there), you will see all kinds of artifacts. Some of these are represented in this diorama. One of the things to keep in mind is that the Utes adopted and adapted tools and ways of doing things from many other groups. They traded and interacted in many other ways with other Indian bands and with the Spanish and other Euro Americans as they entered this once remote region.

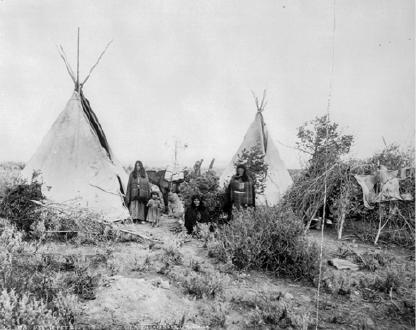

Ute Wickiups & Tipis

"For years, the Utes lived in wickiups, conical timbered structures covered with boughs, branches, brush and occasionally hides. These were used widely across the mountain and basin region by several [Indian] groups, but in Colorado are usually associated with the Utes. Many [wickiups] are found in timbered areas above 6,000 feet elevation, the homeland territory for most Ute bands. Several types of wickiups are known in Colorado; some are similar to [the example to the bottom]--freestanding structures of cut poles arranged in a conical shape with the pole [ends] resting on or slightly pushed into the ground. Stones sometimes ring and stabilize the poles. A second group is built around and supported by living trees, often formed with flat roofs and straight sides or as lean-tos against a live tree. Not all wickiups were dwellings. Some might have been temporary habitations for bands as they traveled, while others were 'war lodges.' Once erected, wickiups were usually left in place and revisited over several decades by hunters, war parties and travelers. Many scholars believe that wickiups were the only habitation structures built by the Utes prior to European contact. Although the Utes living east of the Green and Colorado Rivers were noted in the historical record as early as the 1620's, they were not described or named until the 1776 expedition of Spanish explorers Dominguez and Escalante into the region. In his report, Escalante notes stick huts of the 'Yutas' which probably identified wickiups, as his report also discusses tipis with a differing description. With the exception of the Escalante document, little is known of wickiups until the early 1800's, by which time the structures were less frequently built. As the horse came to change Ute lifestyles near the end of the 1700's, and within decades, the people began to adopt the hide or cloth tipi from the Plains tribes, as it was more easily moved to new locations. By 1800, most wickiups had been abandoned and the tipi was predominant in the region, often erected next to timber structures in regularly-visited camps."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

"This is a portion of one of the few complete surviving examples of Ute building, and a rare museum holding. The wickiup, found near the top of Cochetopa Pass in Saguache County, was photographed and described in a survey of such structures in the late 1930's by Harold Huscher, whose field findings were deposited with the Denver Museum of Natural History in 1939. . . ."

"In 1978, with the wickiup's preservation in its original location threatened, the staff of the Colorado Historical Society's Office of the State Archeologist carefully photo- documented the structure and recorded its disassembly. Individual poles were numbered, the information stored in agency records and the components housed with the collections of the Colorado Historical Museum. Archeological testing of the site was completed, but no artifacts or additional features were located."

Source: Text from Ute Indian Museum

Ute Wickiups & Tipis

The tipi shown to the right is one of two on the grounds of the Ute Indian Museum. As you have read, wickiups rather than tipis were the primary Ute shelter at least until the Utes acquired horses. The horse changed the Utes' lifestyle in many ways. They were able to travel greater distances more quickly. They could now go out on the plains east of their mountain homelands in search of buffalo.

"Across the West, the buffalo was revered and respected by all native peoples. The buffalo lived in herds that often covered the plains as a dark moving cloud. For the Indian cultures of the Great Plains and surrounding regions, the buffalo was the source of almost all food and raw materials of life. No other animal provided in one being so much of the vital support of human life as did the buffalo, the 'Gift of the Great Spirit.'"

"The buffalo symbolized power, successful hunting and continuity of life by providing materials for so many items of daily use. Hides were tanned for robes, tipis and bags, bones were cleared of marrow and fashioned into tools, brains were used in tanning and the tongue was savored as a feast delicacy."

Because Ute tipis coverings were most often made of buffalo hides (at least in the 1800's), very few have been preserved. By the end of the 19th century, most native groups began to use cloth canvas for tipi coverings. The tipi below is made from canvas.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

"Unlike the individual stalking of deer, elk or antelope, the hunt for buffalo was usually a group effort. Before the arrival of the horse, much buffalo hunting took the form of ambush near water holes, brush pits, cliffs, and canyon or sand traps. The horse allowed extended travel in the search for large game and the development of hunting techniques suited to the open plains. Lifeways for many Plains Indian groups and for the Ute bands changed to accommodate the increased access to herds and success of the hunt from the speed, flexibility and distance possible as mounted hunters."

"The Utes sought buffalo on the plains, but also pursued the smaller herds of the Great Basin of Utah and the high mountain parks of Colorado. The coming of the white men and increased pace of buffalo hunting reduced the herds almost to extinction; they were gone from the San Luis Valley and Middle Park by 1876 and from North Park before 1880."

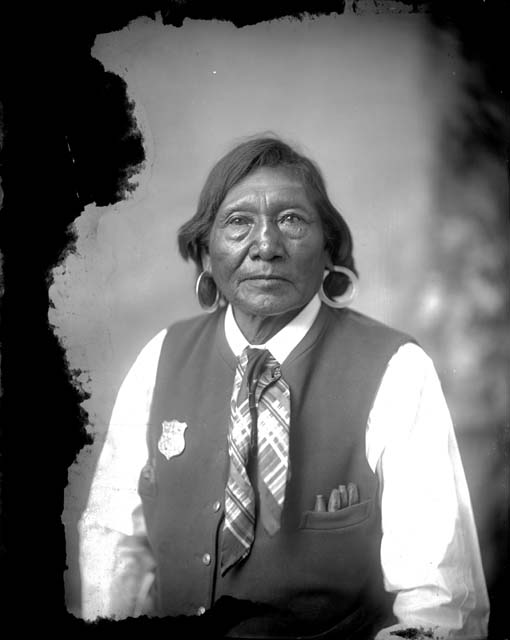

Ute Chief Buckskin Charlie

"Born in 1840, Buckskin Charlie was half Ute and half Apache. He grew up among the [Ute] Capote band at a time when his culture was in tremendous flux. Many times in his adult life, he traveled to Washington, D.C., and other cities where he met with government officials to decide the fate of the Utes. On one of his trips, he even marched in [President] Theodore Roosevelt's inaugural parade."

"At the age of ninety-six, one of the most influential of the Ute leaders died, taking with him the memories of his long life. Ouray had chosen Buckskin Charlie, also called 'Sapiah' or 'Charlie Buck,' to be his successor after his death. Buckskin Charlie continued to guide his people along the same course that the elder leader had so carefully cleared--one of moderation and care."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

"Like Ouray, Buckskin Charlie worked for peace between his people and the whites. Realizing that white rule was inevitable, he counseled his tribes people to cooperate with the whites and accept the land allotments offered by the United States. At the same time, he encouraged the Utes to retain their old ways of life. He was especially proud of the leather tanning and beadwork for which his people were famed, and he usually appeared in public dressed in Ute native clothing."

Ute Chief Buckskin Charlie's Vest

The vest shown in the photo belonged to Buckskin Charlie, a sub-chief of the southern Utes. The vest is made of buckskin, with beadwork in green, red, blue, and yellow. The beads are formed in geometric patterns and with American flags. The vest is lined with printed cotton and the bottom of the vest is lined with metallic fringe. The vest is dated sometime before 1915 because the Italian beads were not available after that time. Barry Sullivan, a close friend of Buckskin Charlie, donated the vest to the Colorado Historical Society in 1961.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Chief Buckskin Charlie's Headdress

The headdress in the photo belonged to Buckskin Charlie. It was given to Barry Sullivan in about 1936 when he was dying and was adopted into the tribe. Marie Andrews donated the headdress to the Colorado Historical Society in 1961. The headdress has a single trail of eagle feathers mounted on buckskin. The feathers are dyed orange and light blue. The headband at the top of the bonnet has white, light blue, red and yellow beads.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Women's Clothing

In the photo below is a buckskin dress that once belonged to Ute Chief Ignacio's wife Lauriano-I-You. The dress was made of two large pieces of buckskin. The cape-like sleeves were made from the hind legs of an animal. The bottom of the skirt is fringed while the top is painted with yellow ochre and outlined in blue, red, and green bead rows. The type of beads indicate that the dress was made sometime between 1870 and 1915. Pieces of fur are attached front and back at the neckline. To the left of the buckskin dress are Ute women's leggings. The lower parts of both leggings have decorative beadwork on a white background. The beads were of Italian origin. This fact helps date the leggings sometime between 1870 and 1915.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

The women's leggings (left middle of the photo) were made of buckskin. The beads are yellow, blue, red, and green on a white background. Many of the beads were or Italian and Czecheslovakian origin. Brass bells and silver buttons (or studs) are also used to decorate these leggings. The women's moccasins (lower middle of the photo) were also made of buckskin. Beads of many colors are used to make geometric flower designs on a white background. Again, a number of collectors and donors have made these artifacts available to the Colorado Historical Society so the general public can enjoy and appreciate the superb craft work of the Utes.

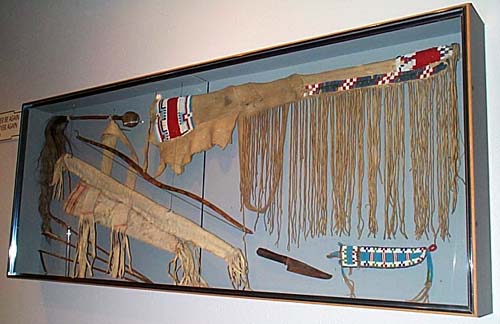

Ute Men's Clothing

The objects displayed on the board (left part of photo) are a pair of Ute men's leggings. These leggings were made of buckskin and are decorated with buckskin fringe. Each legging was painted with yellow ochre and was decorated with geometric green and red beads. These leggings were probably made sometime between 1860 and 1870. The Colorado Historical Society has had these in its possession since 1888. The green cloth (to the right of the leggings) is called a breech clout (sometimes also called a loin cloth). The cloth is green wool and is decorated with red, orange and blue ribbon. The white ribbon binding was sewn by machine. The date of the breech clout is placed sometime between 1860 and 1910.

The Colorado Historical Society acquired the Ute artifacts in the men's clothing display

case in several ways. For example, Ute Chief Severo gave his scalp shirt to Charles

Stobie for safe-keeping shortly before Severo's death in 1913. Bob Webb purchased

the shirt in about 1961 and in turn sold it to the Historical Society the next year.

Indian scout Sam Todd said that a Ute friend of his gave him the Southern Ute war

bonnet. A relative of Todd's, Bessie Jo Quimby, gave the war bonnet to the Historical

Society in 1982. The historical society acquired the other items in this display case

through gift, purchase, and loans from a number of people.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

You can see several articles of Ute men's clothing in this photo:

Vest -The purple vest in the foreground is made of corduroy and has metal and glass bead

decoration. The beads are Italian (from Venice).

Feather War Bonnet - At the back right of the photo is a Ute feather war bonnet. It is made of several

kinds of feathers, including eagle feathers. It was made about 1879-1883.

Scalp Shirt - At the back left of the photo is a Ute scalp shirt. This one belonged to Ute Chief

Severo. Locks from full scalps were used only on a man's best shirt. These shirts

were only worn at council meetings and other important occasions.

Objets of Ute Life

The top-most item in this jewelry display case is a Ute woman's collar. The collar has a yellow background with netted beading of red strips and diamonds in both red and blue. It is probably Ute-made but of an Apache design. The woman's necklace to the right is made of twelve hair pipes (hollowed out bone), which are strung on rawhide. Between each hair pipe is a group of three brass beads (one group has four). This necklace was probably made sometime in the 1880's or 1890's. The necklace in the lower middle of the display case is made up of six strands of juniper berries. The berries are dark brown in color and are strung on cotton thread. This necklace was made sometime after 1860. There is no information about the necklace on the left.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

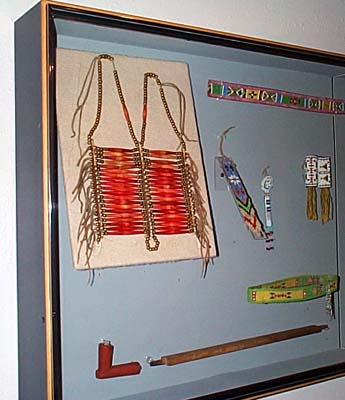

Objets of Ute Life

The artifact in the upper left corner of the display case is a breast plate. The breast plate was made by either Ute or Teton Sioux Indians, sometime between 1880 and 1910. The breast plate is composed of red dyed hair pipe bones and each bone is bordered by two or three brass beads. There are two rows each with twenty hair pipe bones and brass beads strung on rawhide. The carved pipe at the bottom of the display case dates from about the same period as the breast plate (1880-1910). The stem is made of wood and has a rectangular shape. The L-shaped pipe bowl is made of a stone material. This item was found in southern Colorado. By the way, it is customary among Indian tribes to keep the pipe bowl and stem separated when the pipe is not being used.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Weapons And Tools

In the top right hand corner of the display case is a Ute rifle casing. It is made of buckskin with buckskin fringe and includes a variety of beads and wool cloth. The donor's father, Allen Haskill, got the casing from an Indian believed to be Ute. Haskell was a gate keeper on a toll road between Ridgway and Placerville, Colorado. The Indian sold this casing to Haskill to pay the toll and for pocket money. In the bottom right hand corner of the display case is a knife and knife sheath. The knife has a wooden handle and the blade was made from sheep shears in about 1893 (probably by Apache Indians). The knife sheath is made of rawhide and is beaded on one side. This item is on permanent loan to the Ute Indian Museum.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

On the left side of the display case you can see several items important to the Utes.

Quiver and Bowcase - The bow case (just under the bow in the photo) is made of buckskin and sewn with

buckskin thongs. The quiver (just below the case) is also made of buckskin and is

fringed and painted with several colors.

Bow and Arrows - The bow is made of wood and is backed by sinew to give the bow more strength. The bowstring is also made of sinew and is about three and a half feet long. The arrows are also wood and the iron point and feathers are attached to the wood with sinew.

"Skull Cracker" - The skull cracker (or war club) has a wooden shaft, a large stone at one end, and a horsehair tail at the other end. Because the decoration is rather simple, it is believed that the club could have been made before 1800.

Ute Cradle Boards

There are several items in this display case that may be of interest to you.

Cradle Board - This is a typical Ute cradle, dating from the period 1885-1900. The white color at the top of the board means this was a boy's cradle.

Ute Boy's Vest - The green boy's vest to the right of the cradle dates from the 1890-1915 period. It is probably not more recent than 1915 because the Italian beads used to decorate the vest were not available after that date.

Sling Shot - This sling shot (above the vest) was used as a boy's toy. It was made in about

1905 from commercial leather.

Moccasins - Child-sized moccasins can be seen at the bottom of the display case. These were

made of buckskin and may have been burial moccasins.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Cradle Boards

The Colorado Historical Society acquired these artifacts over a long period of time. They also received these items in a number of ways. In some cases, the Historical Society purchased the items. This was the case, for example, with the Ute boy's moccasins and vest and the Ute girl's toy cradle and doll. Another way the Historical Society has acquired such artifacts is through donations and gifts from many people. For example, the boy's sling shot was a gift of the Joseph Smith family (Smith was Indian agent for the Southern Ute Tribe in the early 1900's). The girl's dress was donated by Mrs. L. D. Bax. Verner Reed gave the infant girl's cradle board to the Society in 1930. Whatever the method, it is important that these kinds of artifacts are collected, preserved, and used to increase our knowledge of the past.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

This case displays artifacts that belonged to Ute girls.

Ute Girl's Cradle Board - The ochre color of the cradle board means that this belonged to a Ute infant girl.

Toy Cradle Board - Just below the buckskin dress, you can see a toy cradle board. Between the cradle

board toy and the actual cradle board, you can also see a doll. Ute girls played with

both.

Cradle boards were an infant's secure home for the first months or year of life.

Carried on a mother's back, the child was portable, safe, and easily fed. For mothers

who had much work to do, cradle boards provided supervised day care for Ute infants.

Girl's Clothing - The case also displays several items of girl's clothing. These include a buckskin

dress, two kinds of girl's moccasins, and decorative armbands.

More Ute Artifacts

This display case shows many interesting artifacts that Utes used in their everyday lives. These objects also reflect important aspects of the Ute lifestyle. Two things stand out in particular. First, many Ute artifacts reflect the fact that the horse was at the center of Ute culture (think of the pack saddle and saddle bags, for example). Second, the water bottles reflect the relative dryness (or aridity) of the regions in which the Utes lived. We have seen that many objects displayed in places such as the Ute Indian Museum were donated to or purchased by the curators. This case shows a third way that artifacts are acquired and displayed. The "possible bags," for example, is on extended loan to the museum (since 1931!).

You can see three kinds of water jugs or bottles in the photo to the bottom. The largest bottle (and farthest away in the photo) was actually a basket that was covered with pitch (made from tree sap) both inside and outside. The black items on this basket are handles made of horsehair. This type of bottle was common among many southwest Indian bands besides the Utes. The darkest bottle was obtained at the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation. It was also "pitched" and has a leather strap attached to it. The smallest bottle has a rawhide thong handle and was "pitched" inside. In each case, the pitch was used to make the baskets (or bottles) waterproof.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

More About This Topic

Among the Ute artifacts you can see in this view are the following:

Possible Bags - When you think of a possible bags (lower right hand corner of the display case),

think of a back pack or suitcase. This bag was made of buckskin and decorated with

a variety of beads.

Sash - The three color sash (red, cream, and blue striped cloth) is a Hudson's Bay Trapper's

Sash. It once belonged to famed scout Kit Carson.

Pack Saddle - The object in the left front of the display case is a pack saddle, which is made

from wood.

Saddle Bags - The blue beaded buckskin object at the back of the display case is saddle bags.

The Ute Bear Dance

The diorama at the Ute Indian Museum depicts the Utes performing the Bear Dance.

"When the first thunder of spring rumbles through the sky, it is time for the Bear Dance. According to the elders, families gather in the spring to set up camp and prepare for the event. The men of the bands prepare the Bear Dance corral and the spaces for the dance activities, and the women create the family's festive clothing for the several-day celebration. When the music starts, the women choose their partners. For several days, lines of dancers move back and forth across the corral to the rhythm of the morache and drum."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Their Own Words

"While not of direct religious significance, the Bear Dance is among the older Ute ceremonies. Its origins reflect the connection between human and animal life in the Ute past. First recorded by the Spanish, the tradition of the dance was long established by the 1600's. Ute families pass down variations of the story of the dance's origin, but all agree that the Bear showed the Utes how to dance, taught them the songs and instructed them on when and where to hold the dance. As the dance closes, all men and women know to leave the eagle plumes they have worn throughout the even on a cedar tree planted at the east entrance of the dance corral. The Bear Dance symbolizes the beginning of new life in spring, and the leaving behind of past troubles when the cedar tree's plumes flutter in the breeze."

Source: The text is from the Ute Indian Museum

Ute Bear Dance Instruments

The three items shown in the photo are musical instruments used in Ute Bear Dances.

On the far right is a rattle. The rattle was a dried tan gourd. It has a wooden handle

and traces of green paint has been left on the gourd. It provided music for the Sun

Dance as well as the Bear Dance. The next item is a morache with a stick. The instrument

was a noise maker--called a "Bear Growler"--used in the Bear Dance. It was made of

a wood limb with notches on one side. The Utes ran the rubbing stick (at the bottom

of the morache) over the notches to make the noise. The third item is a drum. The

drum has a bent wooden frame and a rawhide cover (drum head). It was also used for

music in ceremonies and dances. This drum once belonged to "Coup Charlie" a Ute who

lived near Bandad, Colorado.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Chief Colorow

"Colorow belonged to the White River Utes, a northern band noted for its resistance to the invading American culture. Since Colorow's people lived high in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, the remoteness of their territory contributed to their dislike of miners and other white settlers laying claim to the land.

"Led in part by Colorow, the White River Utes played a major role in the Meeker Massacre and its aftermath in 1879. Eight years later, Colorow was also involved in the last Ute war, which arose when a hunting party he was leading some miles away from his reservation was attacked by a hurriedly assemble whilte 'militia' sent to bring a halt to what was claimed to be Ute poaching."

"Well known throughout the state, Colorow was recognized as he led his band of Utes into towns between Denver and Glenwood Springs, trading for supplies and gathering food and other goods from new settlers and local businesses. He was a good teller of tales, and stories about his life and exploits were likewise embellished [added to, often without regard to truth] during his lifetime and in the years following his death."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Chief Colorow's Bow

The bow in the photo is a sinew lined and wrapped wood bow. It has a sinew bow string and rawhide grip. Caroline Bancroft donated the bow to the Colorado Historical Society in 1947. Her grandfather, Frederick Jones Bancroft, was a good friend of Chief Colorow. Shortly before Colorow's death in 1888, he gave Bancroft this bow.

Caroline Bancroft also apparently donated the arrows shown in the case. The arrows have red and black paint at the feather end and black paint at the point end. The arrowhead is made of metal and the point and feathers are held to the arrow's shaft by sinew.

No information is available for the blanket or rug in the photo.

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

Ute Chief Ignacio

"Standing six feet tall, Ignacio was an impressive man who struggled to maintain the Ute lifestyle. He refused to accept the individual allotments of land that the government offered his people, fearing that the communal aspects of Ute life would be lost forever. Instead, in 1895, he persuaded the government to set aside for the Weeminuche a separate tract of land in the extreme western section of the Southern Ute Reservation, now known as the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation. Ignacio died in 1913, leaving his people, now called the Ute Mountain Utes, convinced of the value of maintaining traditional Ute ways."

"In his eighty-five years as a leader of the Weeminuche band, Chief Ignacio helped guide his people through one of the most difficult periods of Ute history. Born in 1828, Ignacio witnessed the increasing influx of whites into Colorado, saw Ute lands diminish after each successive treaty with the United States government, and watched his people starve as their supply of game dwindled."

Photo: Ute Indian Museum

DOWNLOAD THE PDF OF THIS SECTION

The Doing History Project staff wish to thank C. J. Brafford, Director of the Ute Indian Museum, and Anne Wainstein Bond, Director of Collections and Exhibitions at the Colorado Historical Society, for their unflagging cooperation during the production of this virtual tour.

- Colorado Indians Tour One

- Georgetown's Historic Houses

- Georgetown's Historic Stores

- An 1860's Farm

- An 1890's Farm

- Denver's Historic Larimer Square

- Denver's Historic Lower Downtown

- Denver's Historic 17th Street

- The Lebanon Silver Mine

- Denver's Historic Civic Center

- Denver's Historic Uptown District

- Virtual Field Trips Home