The Santa Fe Trail

Traders and merchants in the area around St. Louis had been interested in trading with Santa Fe for years. The major problem was that the Spanish officials governing Santa Fe did not like the idea. Then in 1821, the Mexican people secured their independence from Spanish authorities. At first, the Mexican authorities who replaced the Spanish in Santa Fe resisted trading with the Americans. For one thing, the Mexican authorities imposed taxes on American goods.

Even so, American traders soon began sending wagons full of goods to trade in Santa Fe. In exchange, the Americans traded for silver, furs and hides, and mules and horses, among other things. Before long, a very extensive trade developed between St. Louis and Santa Fe.

St. Louis

This map shows the city of St. Louis in the early 1850s. After President Thomas Jefferson bought the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, St. Louis became important as a trading center. Merchants in St. Louis began an important fur trade with Indians along the Missouri River. Before long, St. Louis merchants also became interested in Santa Fe. These merchants thought Santa Fe might become a large market for their goods and, perhaps, a rich source of gold and silver. However, Santa Fe was in Mexico which was then controlled by Spain. Then in 1821, Mexican nationalists declared their independence from Spain. This opened the door for trade with the Americans.

Photo: Library of Congress, American Memory Collections, Panoramic Maps

More About This Topic

As news of the revolution in Mexico came back to Missouri, several trading parties set out for Santa Fe. William Becknell's party was the first to arrive in Santa Fe, in November, 1821. Becknell made three contributions to the Santa Fe trade. First, he found a workable trail (although Indians and Spanish had been using these pathways for years). Second, he received permission from Mexican authorities to trade in Santa Fe. Third, he made a lot of money. Encouraged by these things, Becknell took another trading party to Santa Fe in 1822. Many other would-be Santa Fe traders followed Becknell's path.

Their Own Words

"Last spring, 1846, was a busy season in the city of St. Louis. Not only were emigrants from every part of the country preparing for the journey to Oregon and California, but an unusual number of traders were making ready their wagons and outfits for Santa Fe. The hotels were crowded, and the gunsmiths and saddlers were kept constantly at work in providing arms and equipments for the different parties of travelers. Steamboats were leaving the levee and passing up the Missouri [River], crowded with passengers on their way to the frontier."

Source: Francis Parkman, The Oregon Trail, 1849. Reprint of 1892 edition, E. N. Feltskog, ed., (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), p. 1.

Outfitting The Wagon Trains

This photograph shows a so-called "bull" train. It was called that because oxen pulled the wagons. These wagons were like those outfitted in western Missouri for trading with Santa Fe. Between 1820 and 1850, several towns in central, and then western, Missouri became centers for outfitting trade wagons bound for Santa Fe. These towns included Franklin, Westport, St. Joseph, and Independence. In the 1820s, Franklin was the first center of trade between Missouri and Santa Fe. By the 1830s, however, Independence became the favorite jumping off place for people traveling to Santa Fe.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Caravans of trade wagons bound for Santa Fe formed about the first of May each year. Local artisans made and repaired wagons and merchants sold provisions and trade goods to the travelers. Horses and mules--and eventually oxen--were the most important items for travelers. Since wagons bound for Santa Fe were fully packed with goods, the wagons were very heavy. The animals pulling the wagons were critical to the success of the traders.

Their Own Words

"It is to this beautiful spot [Independence], already grown into a thriving town, that the prairie adventurer, whether in search of wealth, health, or amusement, [comes] about the first of May, as the caravans usually set out some time during that month. Here they purchase their provisions [foods] for the road, and many of their mules, oxen, and even some of their wagons. . . . in short, load all their vehicles, and make their final preparations for a long journey across the prairie wilderness. . . . Besides the Santa Fe caravans, most of the Rocky Mountain traders and trappers, as well as emigrants to Oregon, take this town in their route. During the season of departure, therefore, it is a place of much bustle and active business."

Source: Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies. 1844. Max Moorehead, ed. (Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1954): 22.

Eastern Kansas

This photo shows a wagon pulled by oxen across an expanse of plains. This scene was probably like many the Santa Fe traders saw on their journey. In many ways, the first hundred miles of the journey to Santa Fe were often difficult. The travelers and their work animals had to be "seasoned" to the journey. Both had to become accustomed to a new environment. In this first hundred miles, the familiar woodlands of the East and Midwest ended as the travelers entered the seemingly flat, tall-grass prairie. Many travelers saw this change as a dividing line between the civilization they left and the wilderness they were entering. In addition, the travelers were learning how to ford streams, endure heavy spring rains and mud, and care for their animals.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Council Grove was a favorite stopping point on the trail to Santa Fe. It was about 150 miles from Independence. It got its name from an 1825 parley between the Osage Indians and a team sent by the U.S. government to survey and mark the trail. For later travelers, Council Grove was the last place on the trail where they could harvest hardwood trees for wagon parts. Since Indians in this region were no longer seen as a menace to travelers, many individuals and small groups met here to form larger companies of wagons. Many wagon companies actually organized themselves here, electing their leaders for the rest of their journey.

Their Own Words

"Our pack-saddles being, therefore, girded upon the animals, our sacks or provision, &c., snugly lashed upon them, and protected from the rain that had begun to fall, and ourselves well mounted and armed, we took the road that leads off southwest from Independence in the direction of Santa Fe. . . . We crossed the stream called Bigblue, a tributary of the Missouri, about 12 o'clock, and approached the border of the Indian domains. All were anxious now to see and linger over every object that reminded us that we were still on the confines of . . . civilization. It was, therefore, painful to approach the last frontier enclosure--the last habitation of the white man--the last semblance of home. . . . Before us were the treeless plains of green . . . . [which] had been . . . the theatre of the Indians prowess--of their hopes, joys, and sorrows."

Source: Thomas J. Farnham. 1841. Travels in the Great Western Prairies. (Poughkeepsie, NY: Killey and Lossing): 12.

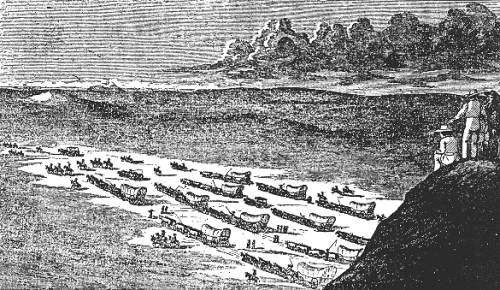

Entering The Great Plains

This photo shows wagons, two-abreast, traveling over the plains. After resting at Council Grove, travelers soon found themselves in increasingly arid [dry] country. They usually camped near small creek or springs when they could. Many of the travelers described these places as oases in the desert, even though worse was yet to come. At this time, most Americans thought of the plains as "the great American desert." Travelers also noticed that the grasses were different from those they knew about in the east. And they noticed that there were few shrubs or trees, except for a few cottonwood trees along some of the rivers and streams.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Depending upon the time of year for travel, the creeks could be difficult barriers for their wagons to cross. Rainstorms and swollen streams were problems for travelers as they moved out on the usually dry plains. This, of course, depended on the time of year in which the journey took place. But since it was common to travel over the plains during the late spring and summer, these weather conditions posed problems. Some of the smaller creeks had steep banks, which turned to mud when it rained hard. The wagoneers often had to use double or triple teams of draft animals to haul the wagons through such streams. This work was very tiring for both humans and animals.

Their Own Words

"We struck camp on the hill. There is a large mound just by us, from the top of which a splendid view is to be had. On one side, to the west, is a wide expanse of Prairie; as far as the eye can reach nothing but a waving sea of tall grass is to be seen. Our the other, for miles around are trees and hills. I went up onto it at sunset, and thought I had not seen, ever, a more imposing sight."

Source: Down the Santa Fe Trail and into Mexico: The Diary of Susan Shelby Magoffin, 1846-1847. Stella M. Drumm, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982): 17.

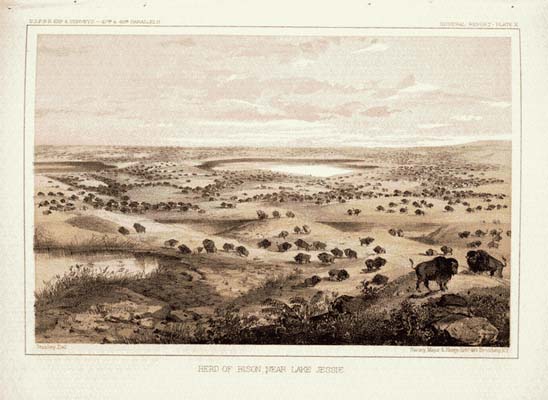

Into Buffalo Country

The drawing shows one of the sights "greenhorn" travelers looked forward to seeing--vast herds of buffalo. Most wagon trains also relied on buffalo and other game for food, at least for much of the trip. For travelers in the 1820s and 1830s, however, buffalo was rarely seen until the trains had nearly reached the Arkansas River. From this point on, at least through the 1840s and 1850s, the travelers usually saw great herds of bison. But the bison posed risks as well as a walking "grocery store." Most of the travelers had little experience hunting buffalo and were not very good at it. On the other hand, many wagon trains hired professional hunters to provide food.

Photo: Library of Congress, American Memory, Congressional Serial Set #1054

More About This Topic

Travelers on the Santa Fe Trail, at almost any time from the 1820s to the 1850s, provide descriptions of themselves or their companions hunting buffalo. Most of those descriptions suggest that the travelers were not very good buffalo hunters. At least that seems to be the case for most besides the professional hunters. Chasing buffalo, whether on foot or horseback, was full of risks. These would-be hunters often got lost; sometimes their horses would break their legs in a prairie dog hole; some encountered Indians. The latter ranged from peaceful and friendly to hostile and dangerous. At certain times of the year, the plains Indians were where the bison were.

Their Own Words

"A few miles beyond a point on the river known as the Caches, and so-called from the fact that a party of traders, having lost their animals, had here cached, or concealed, their packs . . . . We were now, day after day, passing through countless herds of buffalo. I could scarcely form an estimate of the numbers within the range of sight at the same instant, but some idea may be formed of them by mentioning, that one day, passing along a ridge of upland prairie at least thirty miles in length, and from which a view extended about eight miles on each side of a slightly rolling plain, not a patch of grass ten yards square could be seen, so dense was the living mass that covered the country in every direction."

Source: George F. Ruxton. 1849. Wild Life in the Far West. edited LeRoy Hafen, ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951): 248-249.

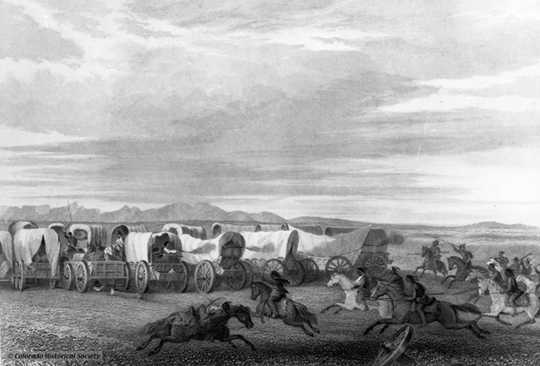

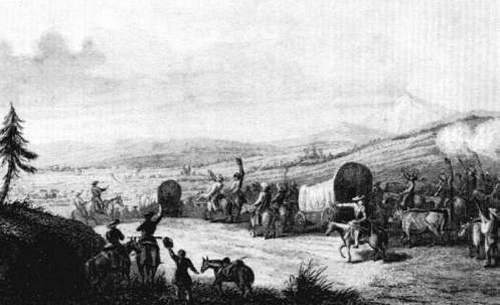

Indian Relations

This drawing shows an attack by Indians on a wagon train. During the first twenty years of the Santa Fe trade, however, these events were quite rare. In the early 1840s, Josiah Gregg reported that early traders on the Santa Fe Trail "but seldom experienced any molestations from the Indians." In the first years of the Santa Fe trade, some traders were attacked by Indians. For the most part, however, the traders either escaped the notice of the Indians or the Indians thought these trains too unimportant to bother. Alphonso Wetmore reported in 1831 that not more than ten lives had been lost during the first decade of the Santa Fe trade.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Perhaps the most important reason plains Indians left Santa Fe travelers alone in the early years was that they devoted much more time to hunting buffalo than they did to warfare. Hunting buffalo brought great benefits at very little risk. Attacking Santa Fe travelers might bring great rewards (especially the manufactured goods they desired), but the risks were much higher. That was so, in part, because most Santa Fe traders assembled large wagon trains for greater protection. Over time, however, the resource base (bison) of the plains Indians began to decline. Grasses and wood resources along plains waterways also declined as Santa Fe travelers and their stock used up these resources. As the Indians' resource based declined, they turned to trading with, requesting presents from, and attacking the wagon trains.

Their Own Words

"Late in the evening of Monday the 24th, we reached the Arkansas, having traveled during the day in sight of buffaloe, which are here innumerable. . . . It is a circumstance of surprise to us that we have seen no Indians, or fresh signs of them, although we have traversed their most frequented hunting grounds; but considering their furtive [secret or sly] habits, and predatory disposition, the absence of their company during our journey, will not be a matter of regret."

Source: William Becknell Diary. 1821. In David White, ed. News of the Plains and Rockies, 1803-1865. (Spokane, WA: Arthur Clarke, 1996): Volume 2, 61-62.

Cimarron River Cut-Off

This drawing shows a wagon train traveling on the Cimarron Cut-off. After traveling along the Arkansas River for a hundred miles or so, travelers had to make a choice of which route they would take to Santa Fe. Most trading companies chose the Cimarron route. This route was about 100 miles shorter than the other route via Bent's Fort and Raton Pass. Travelers had to cross the Arkansas and move south until they met the Cimarron River. Following this river bed put travelers on the south-westerly course which they followed for a while, until they had to strike out across the desert toward Santa Fe.

Photo: Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies

More About This Topic

The Cimarron cut-off was much more suitable for heavy wagons than the Bent's Fort-Raton Pass route. Even so, wagons trains faced many difficulties moving down this route. The cut-off was also much more dangerous than the alternative. First, it lacked water and forage for livestock to a greater extent than the northern route. Second, the cut-off took travelers through the territory of the Kiowa and Comanche Indians. These groups were almost always more hostile and challenging to American and Mexican intruders on their grounds.

Their Own Words

"After following the Arkansas, about eighty miles, we forded it with our wagons, and took a more southerly course toward the Semaron [Cimarron River] . . . . After crossing, we travelled about twelve miles through the sand-hills, and then came into the broad and barren prairie again. The prairie, however, between the Arkansas and Semaron, (a distance, according to our route, of about a hundred miles), was not level, but rather composed of immense undulations . . . a hard, dry surface of fine gravel, incapable, almost, of supporting vegetation. The general features of this whole great desert--its sterility, dryness and unconquerable barrenness--are the same wherever I have been in it."

Source: Albert Pike. 1834. Prose Sketches and Poems. David J. Weber, ed. Albuquerque, NM: Calvin Horn Publisher: 231.

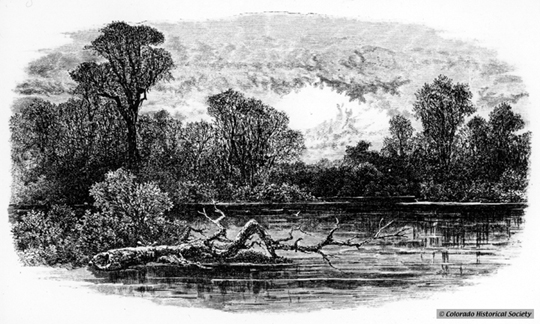

Big Timbers Of The Arkansas

The drawing shows what the "big timbers" of the Arkansas River probably looked like in the early 1800s. Plains Indians survived in winter by breaking up into small bands and retreating to specific kinds of locations within the plains. These places had to have four resources. The Indians needed forage for their horses. They had to have water for themselves and their horses during the driest times of the year (i.e., winter). They had to have fuel and protection from the powerful winds that blew much of the time. These kinds of places were all on plains streams and rivers. Even so, not all sections of every stream or river had all the resources Indians needed. The largest of these places were called "big timbers," and the most famous of these was the "big timbers" of the Arkansas.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

The Big Timbers of the Arkansas River was a grove of cottonwood trees stretching down the river each direction from present-day Lamar, Colorado. The Smoky Hill River, near the present-day Kansas-Colorado boundary had the second "big timbers" and the Republican River, near present-day McCook, Nebraska, had the third. There were, of course, other desirable locations along each of these rivers, the South Platte River, and the tributaries of each. Even so, there were not many places with adequate resources on the great plains. One of the problems that emerged over time was that travelers and traders along the Santa Fe Trail (and other trails as well) were using up the resources of these places. They consumed the wood for their own fires, their stock ate the grass, and they often polluted the water.

Their Own Words

"In winter the Plains Indians, who are very susceptible to cold, remain in their teepees nearly all the time, going out only when forced to do so, and getting back as soon as possible to the pleasant warmth of their homes. Their ponies are wretchedly poor, and unable to bear their masters on any extended scout or hunt. . . . A day which would be death on the high Plains may scarcely be uncomfortably cold in a thicket at the bottom of a deep narrow canyon. Indians, plainsmen and all indigenous animals understand this perfectly, and fly to shelter at the first puff [of snow]."

Source: Richard Irving Dodge. 1883. Our Wild Indians: Thirty-Three Years' Personal Experience among the Red Men of the Great West. Hartford, CT: Worthington and Co.: 501.

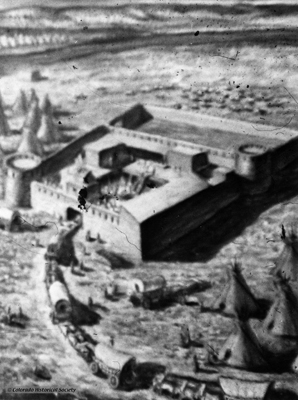

Bent's Old Fort

This drawing depicts the entrance to Bent's Old Fort. Although the majority of Santa Fe traders chose the Cimarron route to Santa Fe, not all did. After the founding of Bent's Fort in the early 1830s, some travelers and traders followed the Arkansas River upstream to the fort. From there, they turned southward through Raton Pass to the settlements in New Mexico. Many of those who chose this route often had smaller, lighter wagons or traveled via mule pack-trains. Over time, Bent's Fort itself became an important trade destination. Traders brought manufactured goods of various kinds to the fort, which were used in exchange for buffalo robes and beaver pelts brought to the fort by both Indian and white trappers and hunters.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Bent's Fort was a center of the Indian trade. Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians, in whose territory the Bent brothers built their fort, formed a very close trading relationship with the Bents. William Bent, the manager of the fort, married Owl Woman, a Cheyenne woman. One result of this union was very friendly relations between these two plains tribes and white travelers and traders. An older brother, Charles, was the driving force of the company. He lived in Taos to look after the company's interests there. Ceran St. Vrain, a partner in the enterprise, also lived in Taos.

Their Own Words

"The fort is a quadrangular structure, formed of adobes, or sun-dried brick. It is thirty feet in height, and one hundred feet square; at the northeast corner, and its corresponding diagonal, are bastions of a hexagonal form, in which are a few cannon. The fort walls serve as the back walls of the rooms, which front inward on a courtyard. In the center of the court is the 'robe press' . . . . The roofs of the houses are made of poles and a layer of mud a foot or more thick, with a slight inclination, to run off the water."

Source: Lewis H. Garrard. 1846. Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955): 42-43.

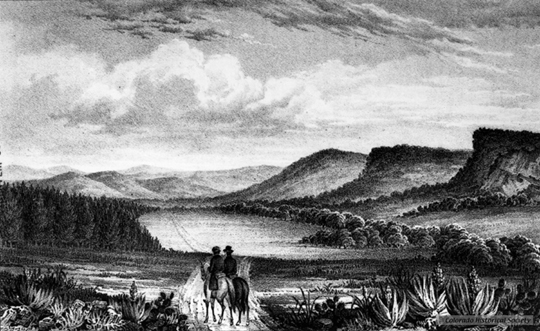

Mountain Raton Route

This is a drawing of the Purgatory River Valley. After stopping at Bent's Fort, travelers bound for the New Mexican settlements still had a ways to go. Most followed a south-westerly course that took them across a desert before they crossed the Purgatory River and followed that stream to the foot of Raton Pass. The Pass itself was full of dangers for the weary travelers. Depending upon the time of year, travelers could experience severe cold and deep snow.

Photo: The Colorado Historical Society

More About This Topic

Travelers and traders with large, heavy wagons usually avoided the mountain route to Santa Fe. But for those with lighter wagons, the trip over Raton Pass could still be difficult. Depending upon the time of year, forage was often scarce for travelers' livestock. Wood for fuel was almost always scarce. U.S. Army Lieutenant J. W. Abert reported seeing the wreckage of wagons near the crest of Raton Pass.

Their Own Words

"On October 21 [1821] William Becknell's trading party "arrived at the forks of the river [where the Purgatoire flows into the Arkansas River], and took the course of the left hand one. . . . [Farther along] We had now some cliffs to ascend, which presented difficulties almost unsurmountable, and we were laboriously engaged nearly two days in rolling away large rocks, before we attempted to get our horses up, and even then one fell and was bruised to death. At length, we had the gratification of finding ourselves on the open plain; and two days' travel brought us to the Canadian [River] fork, whose rugged cliffs again threatened to interrupt our passage, which we finally effected with considerable difficulty."

Source: William Becknell, in David White, ed., News of the Plains and Rockies, 1803-1865, Vol 2 (Spokane: Arthur Clarke, 1996): 64.

Santa Fe

This drawing was made of Josiah Gregg's wagon train arriving in Santa Fe in the late 1830s. The physical distance between St. Louis and Santa Fe was great. The 750 to 850 miles between the two places traveled by horse, mule, or wagon took two months. If that distance was great, the cultural distance between the American traders and their Mexican hosts and customers was probably even greater. It was not that the two peoples were always at odds. Rather, each group found the other to be different in their habits and customs.

Photo: Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies (1844)

More About This Topic

After trade between Missouri and Santa Fe began in the 1820s, Americans enjoyed Mexican hospitality and wanted to take advantage of trading opportunities there. Yet they found much to criticize in the habits and customs of the Mexican people. Mostly Protestants, the Americans did not like the power of the Catholic Church. While Mexican officials often greeted them with cordiality, the Americans did not like the power these officials held over the common people. Mexican officials often seemed to be easily changing--sometimes they were cordial; other times they were uncooperative. Not understanding Mexican culture and circumstances, the Americans were often critical of what appeared to be a lack of hard work and industry.

Their Own Words

"The next day, after crossing a mountain country, we arrived at SANTA FE and were received with apparent pleasure and joy. It is situated in a valley of the mountains, on a branch of the Rio del Norte or North River [now called the Rio Grande], and some twenty miles from it. It is the seat of government of the province; is about two miles long and one mile wide, and compactly settled. The day after my arrival I accepted an invitation to visit the Governor, whom I found to be well informed and gentlemanly in manners; his demeanor was courteous and friendly. He asked many question concerning my country, its people, their manner of living, etc. . . ."

Source: William Becknell. 1821. In David White, ed. News of the Plains and the Rockies, 1803-1865. (Spokane, WA: Arthur Clarke, 1996): Volume 2, 65.

Taos Area

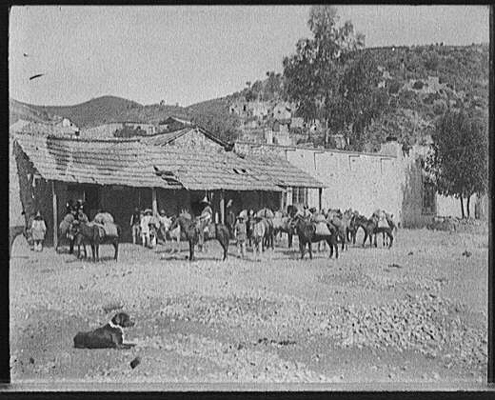

This photo shows a burro pack train in Taos, New Mexico. The town of Taos, about eighty miles north of Santa Fe, was not on the Santa Fe Trail. Even so, it became important in the Santa Fe trade. Taos became a center for the so-called southern fur trade. Trappers and hunters who sought beaver pelts and the hides of other animals used Taos as a place to trade their harvests for new supplies. These supplies included foodstuffs, traps, knives, guns, powder, and lead, as well as clothing. These goods were provided largely by Santa Fe traders who, in turn, bought the pelts and hides from the trappers and hunters.

Photo: Library of Congress, American Memory Collection

More About This Topic

In the 1840s, the population of the Taos Valley was estimated to be about 8,000 people. According to Frederick Ruxton, the valley was fertile and produced very good wheat and other grains. A number of American traders settled in the valley, many of whom opened distilleries to make whiskey. This beverage was called "Taos Lighting" and was important in the trade with trappers and hunters as well as with the Indians.

Their Own Words

"Directly in front of me, with the dull color of its mud dwellings, contrasting with the dazzling whiteness of the snow, lay the little village, resembling an oriental town, with its low, square, mud-roofed houses and two square church towers, also of mud. On the path to the village were a few Mexicans, wrapped in their striped blankets, and driving their jackasses heavily laden with wood towards the village. Such was the aspect of the place at a distance. On entering it, you found only a few dirty, irregular lanes, and a quantity of mud houses."

Source: Albert Pike. 1834. Prose Sketches and Poems Written in the Western Country. David J. Weber, ed. (Albuquerque, NM: Calvin Horn Publisher, 1967): 146.