Seeking Answers

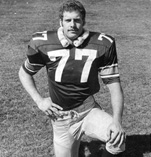

Former teammate’s death prompts Dave Stalls to volunteer for concussion study involving former NFL players

By Steve Luhm (BA-76)

David Stalls wasn’t sure what to do.

David Stalls wasn’t sure what to do.

It was the summer of 1977 and, after four years of starring at UNC, he had been drafted by the Dallas Cowboys — one of the NFL’s glamour franchises.

It seemed like the perfect opportunity for Stalls, who as a defensive lineman at UNC had established himself as one of the best players in school history.

Still, he was torn.

Stalls, who majored in zoology and minored in chemistry, was only one quarter shy of graduating — “Football made me miss a lot of afternoon labs,” he says almost apologetically — and pursuit of a master’s degree in marine biology was his next goal.

When the Cowboys selected him in the seventh round of the draft, however, another door opened.

“Football was not a priority in my life,” Stalls says. “Being drafted was an amazing compliment, but I had to think about whether I was going to do it.”

Two factors helped Stalls decide.

No. 1, the money he earned would quickly erase concerns about paying for graduate school — even if he didn’t stick with the Cowboys.

Stalls received $5,000 just for going to training camp. By making the team, he earned another $22,500, with the possibility of doubling that amount if Dallas reached the Super Bowl, which it did.

“I never imagined making so much money,” he says.

Beyond finances, Stalls had a more personal reason for trying professional football.

“Division II guys always wondered whether we could play with the big guys,” Stalls says. “Part of me wanted to find out. Can I play with the [top] draft choices — guys from the big schools? I wanted to prove myself.”

Of course, there would be a price to pay.

Stalls played football for nearly two decades — including high school, college and eight years in the NFL. It was an era when players were expected to perform, not nurse injuries or worry about their future.

In that regard, Stalls was typical — strapping on his helmet, day-after-day, despite the violent collisions he endured during grueling practices and games.

Concussions?

NFL teams preferred to think of them as an unavoidable hazard of the job. Asked how many times his brain ricocheted around inside his skull so violently that he suffered a concussion, Stalls laughed like someone who already knows the punch line of a bad joke.

“It’s funny,” he says. “Every time you have tests done, they ask, ‘How many concussions have you had?’ My question back to them is, ‘How do you define concussion? All the times you were woozy or only the times you were knocked out on the ground?’ ... I know I was woozy — I saw stars — almost every day.”

Two years ago, Stalls was devastated by the death of former teammate Leroy Selmon. The Hall of Famer suffered a stroke and died two days later.

“He was such a great human being,” Stalls says. “He was always in great condition. He never punished his body with alcohol or drugs. For him to die, it made me look at myself and say, ‘I have to find a few things out.’ ”

Stalls went to a neuropsychological specialist in Denver. He had been increasingly bothered by memory loss and sleeplessness and decided to see if those symptoms were related to past brain injuries.

“I was told, in general, there were some areas of concern,” Stalls says. “But they couldn’t really tell me if they were normal for my age or not. That part of it was inconclusive.”

The quest for answers continued.

****

To find out more about his condition and to help other past, present and future players, Stalls volunteered for a comprehensive research project by a Boston University neurology professor who is studying brain function in athletes.

Dr. Robert Stern is trying to identify indicators that will help diagnose and treat chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. It’s a condition historically connected to boxers, with recognizable symptoms including memory loss, behavioral changes, depression and thoughts of suicide.

Dr. Stern has enlisted 100 former NFL players and, for comparison, 50 athletes from sports where participants don’t commonly bash heads during competition.

The study is ongoing, with final results expected next year.

In January, it was Stalls’ turn to participate. He spent two days in Boston, undergoing “all kinds of memory tests.” In one, he was given 30 seconds to come up with as many words beginning with the letter “f” as possible.

“I thought of four — and two of them were cuss words,” Stalls says. “I thought, ‘Is this just a temporary mind-blank or what?’ It made me wonder. Still does.”

Medical tests are also part of the research study and included brain scans, blood tests, MRIs and a spinal tap, where a large needle is used to drain cerebrospinal fluid from the patient.

“That,” Stalls says, “was not fun.”

The painful spinal tap was easier to endure, however, because the possible benefits of the project are so important to so many people.

“As former players, we all know someone — if they haven’t killed themselves — they’ve lost their mental facilities,” Stalls says. “They just aren’t the same people they used to be and that’s tragic.”

To those who suggest former NFL players knew injuries were part of their sport when they embarked on their careers, Stalls has a chilling message.

“We all knew — by playing — that we were sacrificing our knees, ankles, shoulders, elbows and wrists,” he says. “But we didn’t realize we would be losing our cognitive ability to recognize our families. Maybe we should have, but we didn’t.”

****

After his rookie season, fresh off his Cowboys’ Super Bowl XII win over the Denver Broncos on Jan. 16, 1978, Stalls returned to UNC to earn his degree.

“With fall and spring football in the afternoons, it meant I couldn't finish in the Spring of 1977 as my classmates did,” Stalls says. “So I came back after the January ’78 Super Bowl and finished my last quarter in the spring.”

Since retiring from football, Stalls has gone on to work in such diverse fields as banking, telecommunications, veterinary medicine and marine biology. He also operated a youth center in Denver and became director of Big Brothers and Big Sisters of Colorado, when Selmon’s shocking death in 2011 prompted another change.

“I had a great job with Big Brothers and Big Sisters but realized I needed to be back out on the streets,” Stalls says. “I thought that was where I could make a real difference.”

Today, Stalls operates Street Fraternity, a nonprofit program in Denver that tries to help at-risk young men from their early teens to their mid-20s overcome violent pasts.

“It is a place of brotherhood and personal growth,” Stalls says. “I couldn’t be happier. I feel like this is where I belong.” NV

Read story: Chosen Path Results in Two Super Bowl Rings

Developing Diagnostic Tool: With more testing, the data UNC Professor Igor Szczyrba is collecting through computer models simulating football collisions can be validated and used on the field to help diagnose potential head injuries. Read more at www.unco. edu/news/?5860.