UNC’s ties to Estes, Rocky Mountain National Park span generations as today’s students continue to trek west for recreation, education and the Colorado experience

By Dan England, Photography Courtesy of UNC Archives and UNC Outdoor Pursuits

From a brochure advertising Colorado State Teachers College’s summer school for teachers in 1923: “The teacher wears her life away giving, forever giving, the fineness of her soul to others, dreaming of that nobler social order that is to be, struggling to make herself a part of the progress of the ages, rejoicing in the triumphs of those who have been moulded (sic) by her influence, but seldom taking time to renew those deep sources of being out of which come the power to serve.”

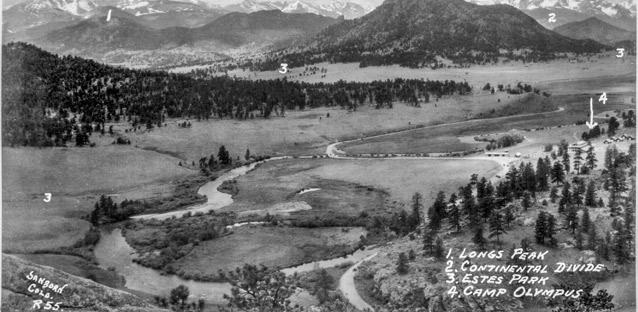

The flowery text flows side-by-side with romantic black-and-white photos of mist-shrouded mountains and lakes. The summer camp drew teachers from throughout the country to respite and rejuvenation in the Rocky Mountains of Estes Park. It was one of the university’s earliest ventures there, but students, faculty and alumni have had many connections to the area since then, aimed at teaching and learning, conducting research and making memories.

Lofty Learning at Camp Olympus

In 1904, when Zachariah Snyder first began to develop his idea for a summer school for adults, Rocky Mountain National Park wouldn’t be established for nine more years. But its appeal as a place that could offer a retreat in an inspiring setting was already clear.

Snyder, the university’s second president, quickly developed a reputation as a national leader in education, says Associate Professor Mark Anderson, the government documents librarian and one of UNC’s historians. Snyder recognized early in his administration that Estes Park was a big selling point for recruitment, but he also saw the inspirational value of learning and exploring the mountains and meadows in and around Estes Park. The summer school’s popularity grew from a daytrip program to a residential program in the institution’s newly built Camp Olympus lodge.

“Camp Olympus furnishes an ideal spot for the tired teacher who seeks wholesome recreation, rest and study under the inspiring natural and social conditions,” the brochure reads.

Named Colorado State Teachers College Mountain School, summer classes ranged from ornithology to music. Tuition for each class was $8, and students could choose two-, four- or six-week sessions. Suitcases were acceptable for personal items, but bulky trunks were stored in Greeley for five cents a day to limit the freight being trucked from Greeley to Camp Olympus.

Though the school sold the camp in 1937 (it became a hotel, in operation today as Olympus Lodge), it left behind lessons that still hold true today. “The fact that the work is interesting and is done with pleasure rather than annoyance does not deter from its educational value,” the brochure reads.

Rix Rendezvous

Robin Rix Blakey’s generation had their college careers at UNC interrupted by World War II. But instead of pulling classmates apart, the time away made them closer. Hoping to foster that connection after they graduated, Blakey (from the Class of 1947), not only acted as the president of the alumni association, but he started a reunion that carried on for decades.

Blakey’s grandson, Jason Brinkley, who graduated from UNC in 2004, says his grandfather took great pride in the reunion, which they called the Rix Rendezvous.

“He loved to talk about it,” Brinkley says.

Blakey started the reunion in the 1960s, Brinkley says, in Estes Park, and it was held at the Lazy T for many years, on the border of Rocky Mountain National Park. The gatherings were held well into the 90s. As classmates died, so did the reunion, but at its height as many as 40 people attended. It was one of the few reunions that seemed to get larger during the years.

This was way before Facebook, which allows you to enter an event and invite 150 people with a click. Blakey had to keep in touch by telephone and keep a list going.

The reunions were usually not much more than old friends catching up, telling old stories and drinking a few beers, but they were the highlight of his year, “other than seeing his grandchildren,” Brinkley says and laughs.

The reunions apparently meant a lot to others as well. When Blakey died in 1998, those same 40 or so alumni attended his funeral, and they started an endowment fund that bears his name.

Self-Study on Old Man Mountain

When Jediah Cummins attended UNC, he thought he was going to college. He didn’t know he would also get a chance to go to summer camp.

When he was a sophomore working as a resident adviser in 2004-05, he attended a staff

retreat at Old Man Mountain. The place has an iconic history with UNC. Probably thousands

of people in hundreds of different groups spent time on the property, which is on

the border of Rocky Mountain National Park. But Cummins fondly remembers it as a summer

camp for slightly older folks, as well as the many students and faculty who would

spend

a few days up there.

“It was a great bonding experience,” he says. “We hiked and sat by a campfire and had s’mores and stayed up way too late. It was a very Colorado thing.”

For Native Americans, it was a vision quest site for an estimated 3,000 years, maybe as late as the 1800s. Tribes such as the Ute, Comanche, Shoshone, Apache, Cheyenne and Arapaho may have used it for the journey that helps people find their spirit guide, which can be an animal or an element like thunder. Since 1998, UNC professor emeritus and researcher Bob Brunswig has identified 1,100 sacred and cultural sites across some 38,000 acres of the park. Sally McBeth, professor of Anthropology and the department chair, has gone to Old Man Mountain with tribal elders and has researched the site. She’s tried to spread the word about the area being a sacred site to teach others to respect it, which means, essentially, leaving things the way they are and keeping it clean. Her anthropology club has also used the site for a retreat. It wasn’t lost on her that her club was essentially doing what those same Native Americans were doing centuries ago, although not nearly to the same spiritual degree.

The U.S. Forest Service had a ranger cabin up there and eventually donated the site to UNC in 1956. Since then, UNC faculty, staff and students have had access to the site and dormitory, using it for group gatherings, a research base and outdoor learning. Outdoor Pursuits uses it frequently for student-orientation trips (see LaUNCh, below) and for courses such as a wilderness first-responder class and an avalanche survival course. Outdoor Pursuits will also offer two snowshoeing trips and two hikes in the spring. The university also uses Old Man Mountain to introduce students (from Colorado residents to international students) to the Rocky Mountains. “It’s amazing to share the experience with their peers,” says Whitney Dyer, assistant director of Outdoor Pursuits. “It’s so special for everyone involved.”

It turned out to be special for Cummins. He’s since been there dozens of times and credits his time on Old Man Mountain with his decision to come back to UNC and work as assistant director of housing services.

“It really reflects the spirit of Colorado,” he says, “and the spirit of UNC.”

Last spring, UNC’s Board of Trustees authorized UNC President Kay Norton to explore the possibility of selling Old Man Mountain. A sale would help ensure future stewardship of the property and land, and stipulate continued use of the grounds for university functions, Norton told the board.

LaUNCh-ing New Students

In the raft, Tarrin Flaherty forgot how to be socially awkward. She was just about to start her first year of college, and the Colorado Springs resident was nervous about that. She doesn’t do well in crowds of new people. But then, through LaUNCh, a freshman-orientation program that groups incoming students together in the outdoors, she found herself in a raft, staring down rapids fed from the peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park. She quickly forgot she was among strangers. These people were her partners. They were her lifesavers. They were paddling through those waves together.

“It was pretty intense,” Flaherty says. “Someone definitely fell off. But we got him back.”

LaUNCh offers students opportunities to explore Rocky Mountain National Park or Never Summer Wilderness. New students spend nearly a week whitewater rafting, rock climbing and doing some community service in the park.

Erin Datteri-Saboski, director of new student orientation, started the program three years ago after having some success at what she calls an “extended orientation” at the University of Indiana, where she worked before joining UNC. When she wanted to build something like that at UNC, all she had to do was look west.

“There weren’t many exciting things in Indiana, but man, we have these mountains here,” she says. “There’s a great resource.”

Putting students in challenging situations in those mountains, such as sleeping in the same tent and facing near-death experiences (or at least it felt that way to Flaherty) helps them make fast friends. As Flaherty says, even a few familiar, friendly faces can help make a big campus feel like home.

“You don’t know a soul,” Datteri-Saboski says, “but then you’ve done this intense experience with these people, and that’s an instant bond.”

The extended experiences cost extra (the trip to Estes was $225) but offer a more in-depth journey than the two-day orientation program offered to incoming UNC students. Only about 30-40 students make the trip — a fraction of the 2,000 incoming freshmen at UNC each year — but there are some amazing outcomes, Datteri-Saboski says.

This year, she added a chance for the students to tour UNC’s arts programs, in case checking out paintings, rather than thrill seeking on the rapids, helps some students bond with their new best friends. Flaherty, no longer a newcomer on campus, led the arts trip this year. It was cool, she says, to help other students make connections like she once did.

“Now those students come up to me and give me awkward hugs.”