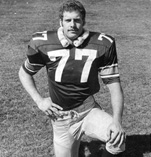

Chosen Path Results in Two Super Bowl Rings

By Steve Luhm (BA-76)

David Stalls was born and raised in Wisconsin but played high school football in Hamilton, Ohio, where he wasn’t exactly a blue-chip recruit.

“This was before the Internet, obviously,” Stalls says. “So I got some books that described all the colleges out there. I went through them, trying to find a medium-sized school in a cool-sounding state.”

Stalls wrote colleges in Maine, Vermont, Montana and Colorado. UNC’s Bob Blasi was the only one to offer a scholarship.

“I thought I would be skiing between the evergreens to class,” he says. “When we pulled into Greeley, I thought, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. This is the flattest place I’ve ever seen.’”

On the field, Stalls was more comfortable.

As a freshman, he started his first game — a 42-6 victory over Colorado Mines.

“I was scared to death,” Stalls says. “But I was pleasantly surprised, too. It was a challenge, but I felt confident after that game. I thought, ‘If the rest of the games are like this, I will enjoy playing college football.’ ”

With Stalls as an anchor on defense, UNC went 29-7 over the next four years, and in the 1977 NFL draft, Dallas took Stalls in the seventh round with the 191st pick.

With no cellphones or social media to break the news, Stalls didn’t discover he’d been drafted until going to lunch at McCowen Hall’s cafeteria. His friends told him. Everyone celebrated.

“It was one of the most ego-boosting things I’d ever experienced,” he says. “I was very proud.”

Stalls’ eight seasons in the NFL were highlighted by three Super Bowl appearances, including wins with Dallas and in Oakland. He was never an All-Star, but he was always a consistent contributor. Stalls’ most difficult year was the strike-shortened 1982 season.

He was a player representative in Tampa Bay, which created animosity with ownership and coaches and made him extremely unpopular with fans. He received death threats.

“It was a long, difficult season,” Stalls says. “The players did not get a lot of sympathy.”

In the offseason, a near-trade to Denver fell through at the last minute, so Stalls again reported to Tampa Bay. But he was released, perhaps in part because of his role in the labor dispute.

Stalls wasn’t out of football for long, however.

The late Al Davis, the iconic owner of the Raiders, called and offered him a chance to play in Oakland. He signed and won his second championship ring in Super Bowl XVIII.

After a year out of the game, Davis convinced Stalls to briefly play again in 1985. But he walked away — this time for good — midway through the season.

“It was just time,” he says. “My knees were so painful and my shoulders were ready to fall off. My body was just done.”

After Stalls was drafted, he wasn’t sure whether to try the NFL or continue his education. But based on the success he enjoyed during his career, he made the right choice.

“Football was very good to me in a lot of ways,” he says. “I met a lot of great people and made a lot of money.” NV

Developing Diagnostic Tool: With more testing, the data UNC Professor Igor Szczyrba is collecting through computer models simulating football collisions can be validated and used on the field to help diagnose potential head injuries. Read more at www.unco. edu/news/?5860.